Kenyan Banks: Profits Without Purpose, SMEs Without Breath

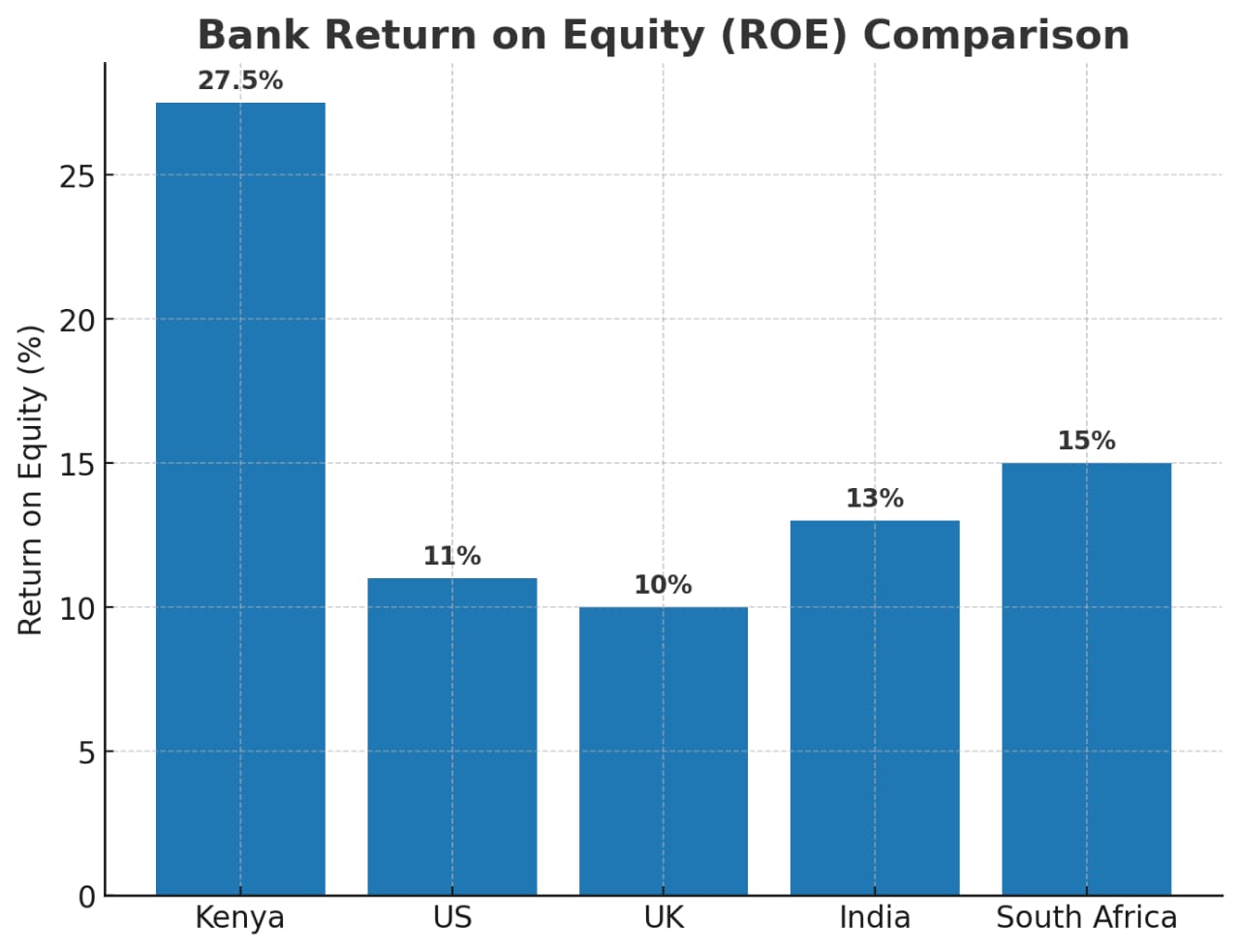

Kenya’s banking sector is celebrated in glossy reports as one of the most profitable on the continent, flaunting a return on equity that ranges between 25% and 30%. Global averages hover at 9–15%, meaning our banks outperform Wall Street, London, and Mumbai. Yet while shareholders smile, Kenyan SMEs—the engine of 80% of employment—are left suffocating without credit.

This paradox is not accidental. Banks are not miscalculating. They are making deliberate choices to pursue easy profits, abandoning the hard, messy, but vital business of financing small and medium-sized enterprises. Instead of nurturing the backbone of Kenya’s economy, banks feed off government borrowing like bloated ticks, swollen with taxpayer-funded securities.

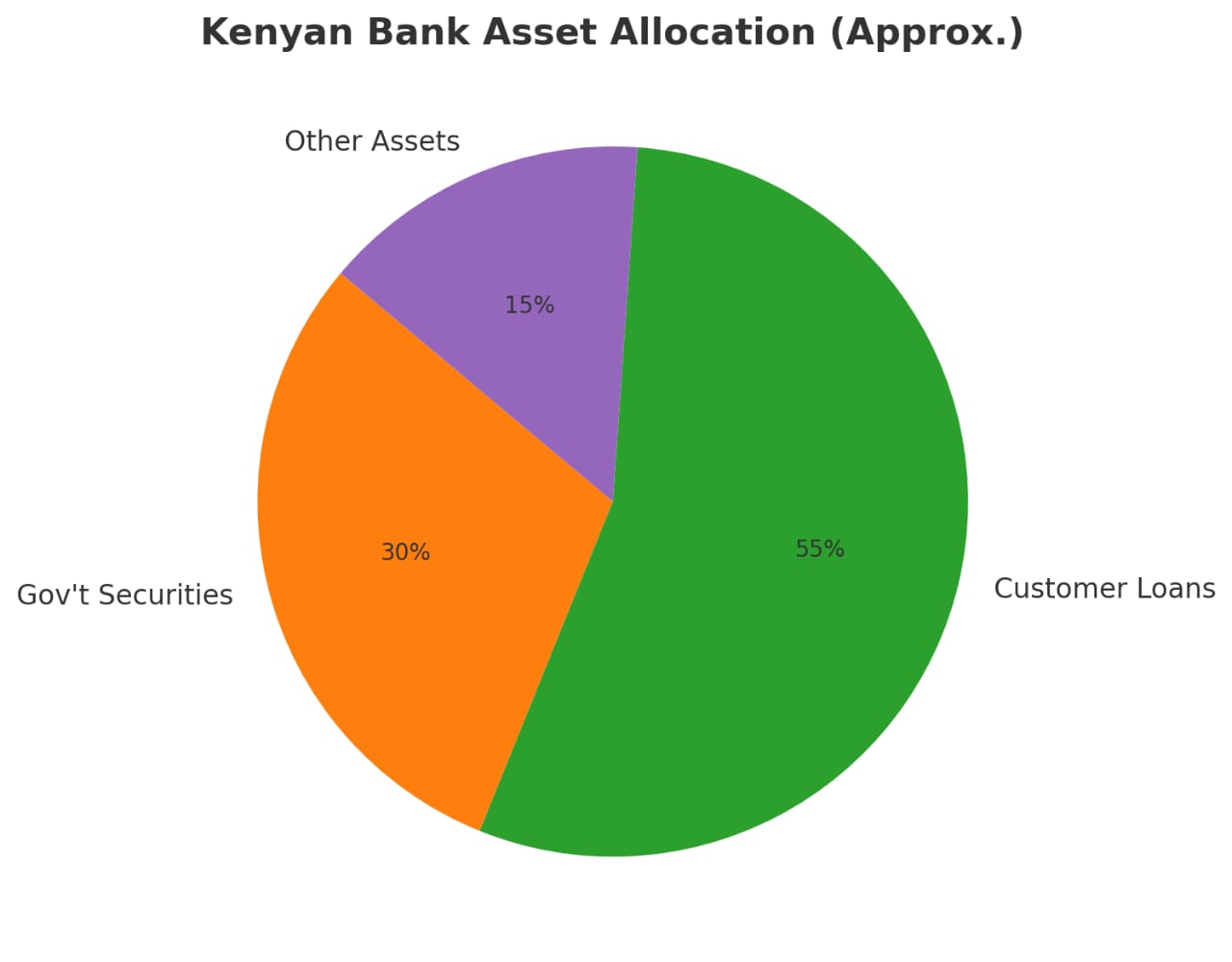

Nearly 30% of Kenyan bank assets are parked in government bonds, a lazy comfort zone yielding 12–15% risk-free returns. Why sweat to understand an SME’s business model, assess risks, and build lasting relationships, when government paper offers the illusion of stability? This addiction to treasury bills has made banks custodians of public debt rather than partners in private enterprise.

Read Also: Standard Chartered Kenya: Cracks Beneath the Shine

The cruel irony is that while banks boast their fortress balance sheets, SMEs—the hair salons, boda repair shops, manufacturers, and farmers—collapse under the weight of inaccessible financing. What was once a promise of inclusion has turned into exclusion. Credit is a fortress with locked gates, and banks hold the keys, refusing to open them.

The defenders of this banking strategy argue it’s rational: why risk defaults when the state guarantees interest? But what they ignore is the larger irrationality of an economy that eats its own tail. A government that crowds out credit leaves SMEs without fuel, leading to joblessness, reduced tax revenue, and eventually, a weaker state that may default on those same bonds.

It’s not just an economic issue; it’s a moral one. How can banks post Sh200 billion in combined profits while the youth in Gikomba can’t access a Sh50,000 loan to expand their stalls? How can bank executives build mansions in Runda while entire factories in Thika shut down for lack of working capital? The profit is soaked in the blood of opportunity denied.

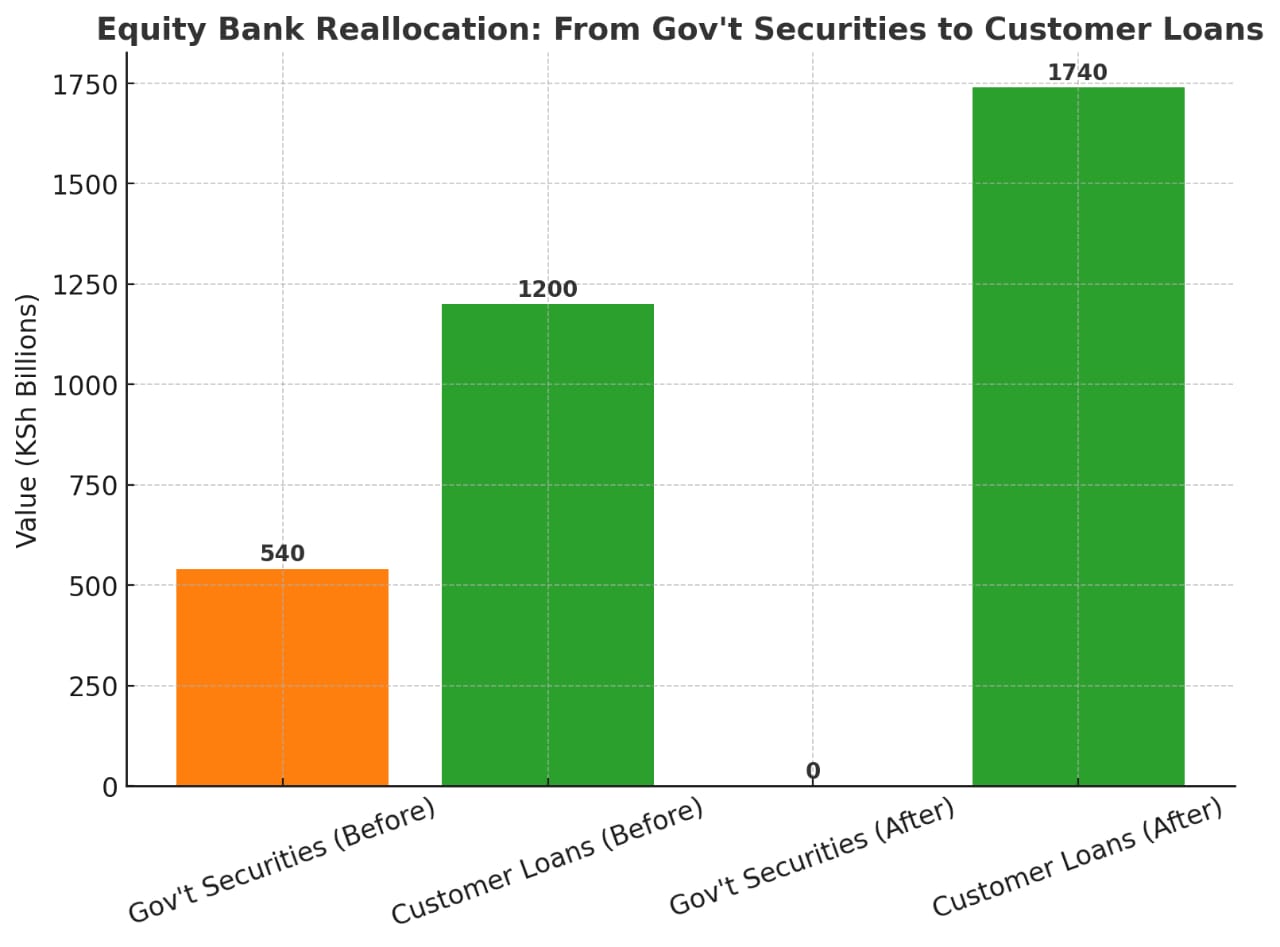

Equity Group’s recent decision to reallocate nearly KSh 540 billion from government securities back into customer loans is a rare glimmer of courage. It signals recognition that banking should serve the economy, not just cannibalize it. But this cannot be Equity alone. Without systemic change, one bold player cannot reform an industry addicted to easy money.

Safaricom adds another twist to this cruel story. Sitting on one of the richest SME data troves in Africa, it knows who earns, who spends, and who has potential. Yet it cannot lend at scale because regulation clips its wings. The result is tragic: data that could unlock trillions in SME lending sits wasted, while the government conjures political gimmicks like the Hustler Fund.

The Hustler Fund, a populist attempt to offer credit, has failed to scale with discipline or sustainability. It is politicized debt, not transformative capital. Instead of empowering hustlers, it shackles them with micro handouts while banks look the other way. It is like tossing a bucket of water on a forest fire and calling it firefighting.

Kenyan banks argue that SME lending is high risk. But risk is not static; it is managed. Banks in Asia lend to SMEs aggressively, using innovative credit scoring and partnerships. What excuse do Kenyan banks have when they have M-Pesa data, CRB data, and transaction histories at their fingertips? The risk narrative is a lazy smokescreen for complacency.

Read Also: Kenya Shilling Overnight Interbank Average Averaged 9.46% During The Week

The structural danger is obvious. Banks that tie their fortunes to government debt live or die by fiscal solvency. If Kenya defaults or restructures, those paper profits evaporate overnight. The so-called “safe play” is a mirage; it is exposure disguised as prudence. Betting on a government drowning in debt is not safe; it is slow suicide.

The human cost is invisible to balance sheets. The woman in Eldoret who cannot expand her tailoring business, the farmer in Bungoma forced to sell maize to middlemen at throwaway prices, the Nairobi start-up stuck in a perpetual infancy because credit is a dream—these stories never make annual reports. But they define the reality of a nation betrayed.

Unemployment, officially at 13%, feels closer to 70% for young people navigating underemployment, gig hustles, and outright joblessness. SMEs are the proven path to solving this, but they cannot thrive on empty rhetoric. When capital is withheld, dreams die. Banks are complicit in burying the future under layers of polished quarterly earnings.

Profit without purpose is theft. And Kenyan banks are stealing the country’s future while wearing expensive suits and sponsoring golf tournaments. They sell us narratives of inclusion, yet their credit policies scream exclusion. They wave CSR cheques at schools, while refusing to lend to the very parents who must pay school fees.

The absurdity deepens when international lenders like the European Investment Bank or AfDB step in to fund SMEs that Kenyan banks shun. Outsiders believe in our entrepreneurs more than our own institutions do. What kind of banking system celebrates foreign capital while ignoring its duty at home?

The corruption of purpose is evident in the smug smiles of executives who boast of record profits. They think themselves geniuses. In reality, they are parasites. Their brilliance lies not in innovation but in exploiting a distorted system where lending to the government is safer than lending to citizens. It is cowardice dressed as intelligence.

Let us strip away the illusion. A banking sector that grows fat while SMEs starve is not strong. It is diseased. It is like a farmer who eats his seed rather than planting it. Short-term gains lead to long-term famine. Kenya cannot afford such a famine, not when over 5 million SMEs struggle daily to stay alive.

The solution is not to demonize profit but to demand balance. Banks must diversify portfolios, commit a significant share to SME lending, and use technology to manage risk. The government must stop crowding out the market with endless borrowing. Regulators must stop being lapdogs and start being watchdogs. Without this, the vicious cycle continues.

At the heart of this mess is a lack of courage. Banks fear SMEs because they require work: monitoring, training, and partnership. They prefer the lazy comfort of treasury bills. But real leadership means confronting difficulty. Real banking means serving communities, not just investors in New York and London.

The satire of our situation is almost biblical. Banks, like Pharisees, preach inclusion while excluding the very people Christ would have sat with: the hustlers, the small traders, the farmers. They worship golden profits while ignoring the suffering of widows and orphans who cannot pay rent. It is hypocrisy of the highest order.

Yet satire must not blind us to possibility. Kenya can shift. Equity’s reallocation shows it is possible. Partnerships between banks and fintechs can unlock new models. Safaricom’s data, responsibly harnessed, could revolutionize credit scoring. SMEs could be funded not as charity but as viable, profitable enterprises.

But for that shift to happen, banks must first admit guilt. They must confess that their profits are blood money, their policies anti-development. They must repent from the addiction to bonds and rediscover their true calling: financing enterprise. Without repentance, they will drag the nation into stagnation.

Let this article be a mirror held up to their faces. Let executives squirm as they read of their cowardice. Let regulators see their own impotence reflected. Let the public understand the theft behind the profits. And let SMEs know they are not crazy—the system truly is rigged against them.

Kenya deserves better. We cannot be a country where banking is world-class, but development is third-world. We cannot clap for ROEs of 30% while our neighbours in Tanzania and Uganda laugh at our SMEs gasping for air. We cannot continue to reward cowardice with awards.

The final insult is this: banks will claim they serve the people because they have “SME desks” and “digital platforms.” Do not be fooled. These are marketing gimmicks, not systemic commitments. The truth lies in the numbers, and the numbers show neglect.

Until the day banks lend to SMEs with the same enthusiasm they buy government bonds, Kenya will remain trapped. Until then, our so-called economic lions are nothing more than well-fed hyenas circling a dying carcass, feasting while the land starves.

Read Also: Kenyan Banks Surpass Ksh 150 Billion Annual Target Lending To MSME

About Steve Biko Wafula

Steve Biko is the CEO OF Soko Directory and the founder of Hidalgo Group of Companies. Steve is currently developing his career in law, finance, entrepreneurship and digital consultancy; and has been implementing consultancy assignments for client organizations comprising of trainings besides capacity building in entrepreneurial matters.He can be reached on: +254 20 510 1124 or Email: info@sokodirectory.com

- January 2025 (119)

- February 2025 (191)

- March 2025 (212)

- April 2025 (193)

- May 2025 (161)

- June 2025 (157)

- July 2025 (226)

- August 2025 (211)

- September 2025 (270)

- October 2025 (297)

- November 2025 (49)

- January 2024 (238)

- February 2024 (227)

- March 2024 (190)

- April 2024 (133)

- May 2024 (157)

- June 2024 (145)

- July 2024 (136)

- August 2024 (154)

- September 2024 (212)

- October 2024 (255)

- November 2024 (196)

- December 2024 (143)

- January 2023 (182)

- February 2023 (203)

- March 2023 (322)

- April 2023 (297)

- May 2023 (267)

- June 2023 (214)

- July 2023 (212)

- August 2023 (257)

- September 2023 (237)

- October 2023 (264)

- November 2023 (286)

- December 2023 (177)

- January 2022 (293)

- February 2022 (329)

- March 2022 (358)

- April 2022 (292)

- May 2022 (271)

- June 2022 (232)

- July 2022 (278)

- August 2022 (253)

- September 2022 (246)

- October 2022 (196)

- November 2022 (232)

- December 2022 (167)

- January 2021 (182)

- February 2021 (227)

- March 2021 (325)

- April 2021 (259)

- May 2021 (285)

- June 2021 (272)

- July 2021 (277)

- August 2021 (232)

- September 2021 (271)

- October 2021 (304)

- November 2021 (364)

- December 2021 (249)

- January 2020 (272)

- February 2020 (310)

- March 2020 (390)

- April 2020 (321)

- May 2020 (335)

- June 2020 (327)

- July 2020 (333)

- August 2020 (276)

- September 2020 (214)

- October 2020 (233)

- November 2020 (242)

- December 2020 (187)

- January 2019 (251)

- February 2019 (215)

- March 2019 (283)

- April 2019 (254)

- May 2019 (269)

- June 2019 (249)

- July 2019 (335)

- August 2019 (293)

- September 2019 (306)

- October 2019 (313)

- November 2019 (362)

- December 2019 (318)

- January 2018 (291)

- February 2018 (213)

- March 2018 (275)

- April 2018 (223)

- May 2018 (235)

- June 2018 (176)

- July 2018 (256)

- August 2018 (247)

- September 2018 (255)

- October 2018 (282)

- November 2018 (282)

- December 2018 (184)

- January 2017 (183)

- February 2017 (194)

- March 2017 (207)

- April 2017 (104)

- May 2017 (169)

- June 2017 (205)

- July 2017 (189)

- August 2017 (195)

- September 2017 (186)

- October 2017 (235)

- November 2017 (253)

- December 2017 (266)

- January 2016 (164)

- February 2016 (165)

- March 2016 (189)

- April 2016 (143)

- May 2016 (245)

- June 2016 (182)

- July 2016 (271)

- August 2016 (247)

- September 2016 (233)

- October 2016 (191)

- November 2016 (243)

- December 2016 (153)

- January 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (4)

- March 2015 (164)

- April 2015 (107)

- May 2015 (116)

- June 2015 (119)

- July 2015 (145)

- August 2015 (157)

- September 2015 (186)

- October 2015 (169)

- November 2015 (173)

- December 2015 (205)

- March 2014 (2)

- March 2013 (10)

- June 2013 (1)

- March 2012 (7)

- April 2012 (15)

- May 2012 (1)

- July 2012 (1)

- August 2012 (4)

- October 2012 (2)

- November 2012 (2)

- December 2012 (1)