Kenya’s Hidden Poverty: A Nation Still Cooking With Firewood in the Age of Satellites

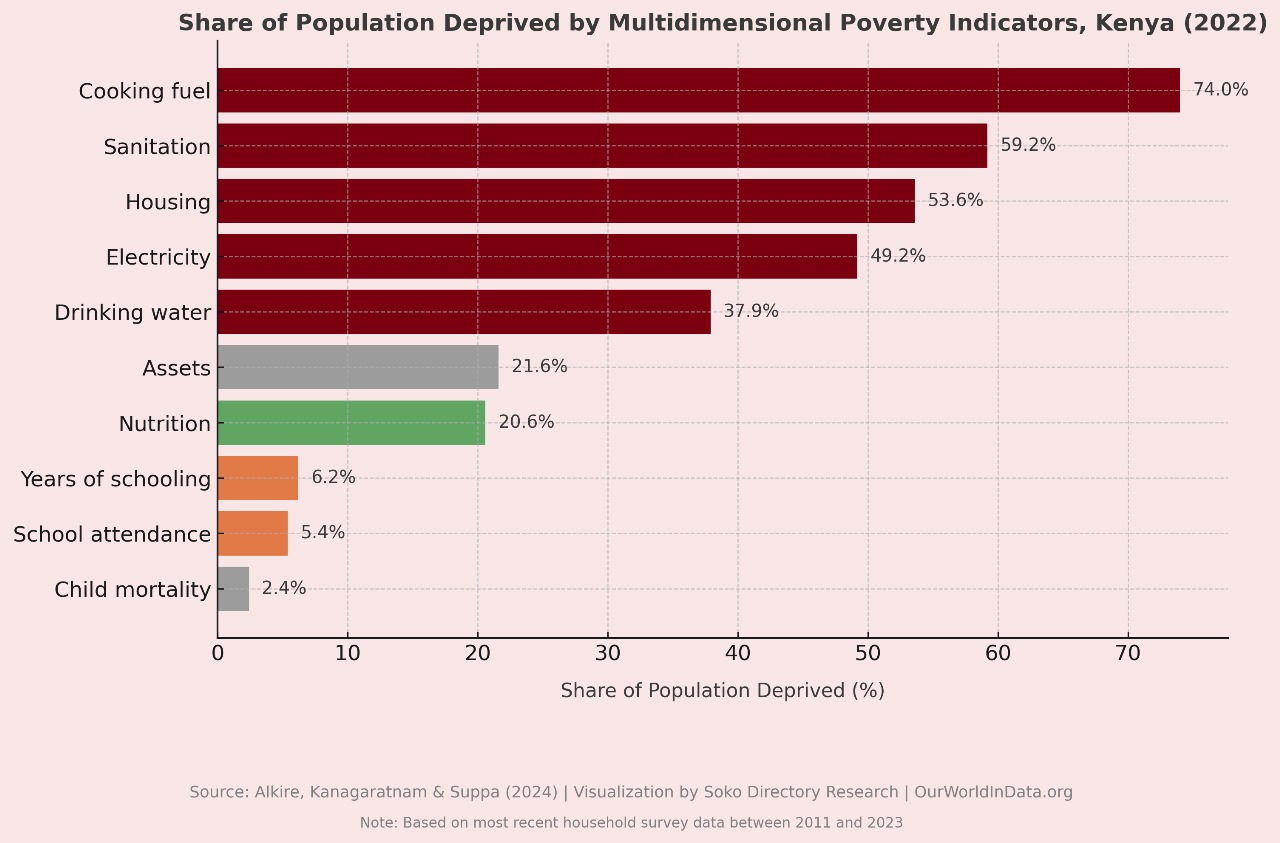

Kenya’s poverty is no longer about the number of people earning below a dollar a day—it is multidimensional, structural, and deeply psychological. 74% of Kenyans still lack access to proper cooking fuel. That means tens of millions wake up every day to chop wood, inhale smoke, and risk respiratory diseases while the elite discuss electric vehicles in air-conditioned boardrooms. This deprivation is not just economic; it’s systemic violence—an indictment of failed energy policy, corruption, and misplaced development priorities that glorify mega-projects over basic dignity.

The 59.2% of Kenyans deprived of sanitation is a moral catastrophe. In a nation that prides itself on digital innovation and mobile banking, more than half of its citizens relieve themselves without proper toilets. Every government since independence has promised clean water and sanitation, yet billions have disappeared through ghost projects. Counties spend fortunes digging boreholes that run dry within months because feasibility studies were falsified to create room for tender looting. Behind every sanitation failure lies a bureaucrat who profited from disease and indignity, while cholera silently reaps lives.

Housing deprivation—at 53.6%—is a reflection of Kenya’s urban hypocrisy. From Kibera to Mathare, Mukuru to Manyatta, millions live in structures unfit for human habitation while politicians build castles and preach affordable housing. The so-called Affordable Housing Program is a monument to corruption, designed to tax the poor into financing the comfort of the politically connected. How can half the population lack decent shelter in a country that claims Vision 2030? This figure unmasks a system where the Constitution promises dignity, but policy delivers despair.

Read Also: The Cruel University of Poverty: Why Being Poor Shows You Life Naked

Electricity deprivation, standing at 49.2%, mocks the promises of “Last Mile Connectivity.” Billions have been poured into rural electrification projects that often end at political boundaries or the homes of chiefs. The sad truth is that electricity in Kenya remains a privilege, not a right. Kenya Power and its allies thrive on inefficiency, inflated procurement, and unending tariff adjustments. When almost half of Kenyans live in darkness, it means half of the nation’s children cannot study at night, half of its entrepreneurs cannot innovate, and half of its dreams remain unlit.

Access to clean drinking water—denied to 37.9% of Kenyans—is a national shame. It’s absurd that a country bordering the world’s largest freshwater lake still struggles to hydrate its citizens. From Turkana to Kitui, the story repeats: dry taps, broken pipes, and water cartels controlling lives. Deprivation here is not just thirst—it’s inequality in its purest form. The rich drink bottled water from imported brands while the poor boil contaminated water in smoky kitchens, risking disease and debt in hospitals that charge for every drop of saline solution.

The data on asset deprivation (21.6%) and nutrition deprivation (20.6%) reveals a deeper malaise—economic exclusion and food insecurity. Millions of Kenyans own no productive assets—no land, no livestock, no savings—and yet the government taxes them as if they do. Food prices rise while wages stagnate, and farmers are crushed under the weight of exploitative middlemen. Malnutrition, both in rural areas and urban slums, tells a story of policy failure. A hungry child is not a statistic—it’s a symbol of betrayal by a state that prioritizes political feasts over school meals.

Education deprivation paints an equally grim picture. Though years of schooling deprivation (6.2%) and attendance deprivation (5.4%) appear lower, the truth is hidden in quality, not quantity. Millions attend dilapidated schools where teachers are overworked, underpaid, and under-resourced. The CBC curriculum is a profit engine for publishers, not a path to enlightenment. The poor send children to schools without books or desks, while politicians’ children learn robotics abroad. This educational apartheid sustains the cycle of multidimensional poverty.

Even child mortality, at 2.4%, cannot be celebrated as a success. Behind that percentage are thousands of preventable deaths—children lost to malaria, hunger, and poor maternal care. Kenya’s healthcare remains transactional: quality for the rich, survival for the poor. The SHIF, like NHIF before it, is a racket in bureaucratic disguise. Health is not just a medical issue—it’s a mirror of governance, and that mirror reflects rot, greed, and insincerity.

When we aggregate these deprivations, the illusion of progress shatters. GDP growth, mobile penetration, and skyscrapers mean nothing when 74% still cook with firewood and 60% cannot use a decent toilet. Kenya’s development model celebrates symbols of wealth while ignoring the foundations of wellbeing. Poverty here is not accidental—it’s engineered to sustain political control, economic dependency, and mental resignation. A population deprived is a population easy to manipulate during elections.

The problem is not just poverty—it’s leadership. Kenya has perfected the art of cosmetic policy: launching, rebranding, and repackaging old failures as new successes. We build expressways while villages drown in open sewers; we digitize land registries while squatters multiply. Poverty persists because those who should end it profit from its continuation. Every deprivation is a business opportunity for someone at the top. Poverty alleviation is no longer about justice—it’s about contracts.

To fix Kenya’s multidimensional poverty, we must dismantle its multidimensional hypocrisy. Cooking fuel, sanitation, housing, electricity, and water are not luxuries—they are the architecture of life. The Constitution promised social and economic rights, yet our politics has turned them into privileges. The poor are not poor because they are lazy—they are poor because policy was designed to keep them so. Until Kenyans realize that deprivation is political, not natural, they will continue voting for their own suffering, mistaking handouts for hope and oppression for order.

If poverty had a face in Kenya, it would not be in the slum—it would sit in Parliament, smile on TV, and tweet about development while children inhale smoke and mothers fetch dirty water. That is the cruel paradox of our time. True progress will begin the day Kenyans rise to ask why 74% cook with smoke while the leaders dine in luxury—and refuse to accept excuses wrapped in statistics.

Read Also: Love Without Stability is Poverty in Disguise: Why Financial Literacy Must Precede Dating

About Steve Biko Wafula

Steve Biko is the CEO OF Soko Directory and the founder of Hidalgo Group of Companies. Steve is currently developing his career in law, finance, entrepreneurship and digital consultancy; and has been implementing consultancy assignments for client organizations comprising of trainings besides capacity building in entrepreneurial matters.He can be reached on: +254 20 510 1124 or Email: info@sokodirectory.com

- January 2025 (119)

- February 2025 (191)

- March 2025 (212)

- April 2025 (193)

- May 2025 (161)

- June 2025 (157)

- July 2025 (226)

- August 2025 (211)

- September 2025 (270)

- October 2025 (110)

- January 2024 (238)

- February 2024 (227)

- March 2024 (190)

- April 2024 (133)

- May 2024 (157)

- June 2024 (145)

- July 2024 (136)

- August 2024 (154)

- September 2024 (212)

- October 2024 (255)

- November 2024 (196)

- December 2024 (143)

- January 2023 (182)

- February 2023 (203)

- March 2023 (322)

- April 2023 (297)

- May 2023 (267)

- June 2023 (214)

- July 2023 (212)

- August 2023 (257)

- September 2023 (237)

- October 2023 (264)

- November 2023 (286)

- December 2023 (177)

- January 2022 (293)

- February 2022 (329)

- March 2022 (358)

- April 2022 (292)

- May 2022 (271)

- June 2022 (232)

- July 2022 (278)

- August 2022 (253)

- September 2022 (246)

- October 2022 (196)

- November 2022 (232)

- December 2022 (167)

- January 2021 (182)

- February 2021 (227)

- March 2021 (325)

- April 2021 (259)

- May 2021 (285)

- June 2021 (272)

- July 2021 (277)

- August 2021 (232)

- September 2021 (271)

- October 2021 (304)

- November 2021 (364)

- December 2021 (249)

- January 2020 (272)

- February 2020 (310)

- March 2020 (390)

- April 2020 (321)

- May 2020 (335)

- June 2020 (327)

- July 2020 (333)

- August 2020 (276)

- September 2020 (214)

- October 2020 (233)

- November 2020 (242)

- December 2020 (187)

- January 2019 (251)

- February 2019 (215)

- March 2019 (283)

- April 2019 (254)

- May 2019 (269)

- June 2019 (249)

- July 2019 (335)

- August 2019 (293)

- September 2019 (306)

- October 2019 (313)

- November 2019 (362)

- December 2019 (318)

- January 2018 (291)

- February 2018 (213)

- March 2018 (275)

- April 2018 (223)

- May 2018 (235)

- June 2018 (176)

- July 2018 (256)

- August 2018 (247)

- September 2018 (255)

- October 2018 (282)

- November 2018 (282)

- December 2018 (184)

- January 2017 (183)

- February 2017 (194)

- March 2017 (207)

- April 2017 (104)

- May 2017 (169)

- June 2017 (205)

- July 2017 (189)

- August 2017 (195)

- September 2017 (186)

- October 2017 (235)

- November 2017 (253)

- December 2017 (266)

- January 2016 (164)

- February 2016 (165)

- March 2016 (189)

- April 2016 (143)

- May 2016 (245)

- June 2016 (182)

- July 2016 (271)

- August 2016 (247)

- September 2016 (233)

- October 2016 (191)

- November 2016 (243)

- December 2016 (153)

- January 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (4)

- March 2015 (164)

- April 2015 (107)

- May 2015 (116)

- June 2015 (119)

- July 2015 (145)

- August 2015 (157)

- September 2015 (186)

- October 2015 (169)

- November 2015 (173)

- December 2015 (205)

- March 2014 (2)

- March 2013 (10)

- June 2013 (1)

- March 2012 (7)

- April 2012 (15)

- May 2012 (1)

- July 2012 (1)

- August 2012 (4)

- October 2012 (2)

- November 2012 (2)

- December 2012 (1)