Kenya’s Road Carnage Is Mass Murder by Negligence: Why Traffic Offences Must Be Made Capital Offences Now

Kenya is bleeding on the tarmac, and we have normalised it. We say “ajali” the way we say “mvua imenyesha”—as if death is weather, as if shattered families are just background noise to our daily hustle. Yet road crashes are not fate. They are policy failure, enforcement collapse, and citizen indiscipline—repeated every day, in broad daylight, with receipts.

The numbers alone should terrify us into action. In 2025, Kenya recorded 4,458 road fatalities, up from 4,311 in 2024, with pedestrians carrying the heaviest burden—1,685 deaths. That is not “bad luck.” That is a national emergency we have chosen to tolerate.

Zoom out and the pattern is even clearer: road traffic deaths globally are about 1.19 million a year. The difference is not that Kenya is cursed. The difference is that other countries treat road safety like the public-health and law-enforcement crisis it is—while we treat it like a seasonal inconvenience.

Every Kenyan already knows the causes, because we watch them every day. Reckless overlapping as if lanes are suggestions. Forceful overtaking into oncoming traffic as if other people’s lives are negotiable. Climbing lanes used like express lanes. Drivers pushing beyond safe hours, exhausted and jittery, still speeding because “time ni pesa.”

Then add the poison that makes it all worse: corruption. Licences obtained through bribery and shortcuts. Driving schools that churn candidates through “passing” instead of training. Enforcement that is sometimes a road-safety operation and sometimes a revenue collection exercise. It is not just that people break the rules; it is that the system is structured to let them.

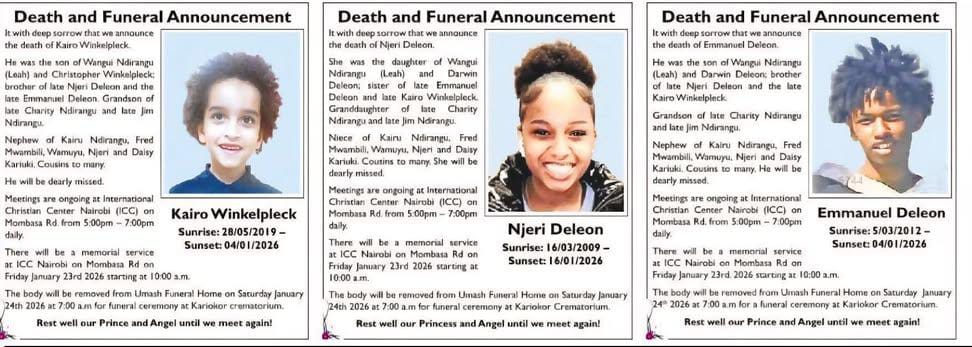

And that is why families are being wiped out in a single moment—whole futures erased because someone wanted to save five minutes, or make a few shillings, or avoid a fine. On January 4, 2026, a US-based Kenyan family visiting home lost three children in a crash along the Nairobi–Nakuru/Naivasha highway: Emmanuel DeLeon (13), Kairu Winkelpleck (6), and Njeri DeLeon (16).

These are not statistics; these are names that now belong to a mourning calendar.

If you need another image of how road carnage collapses generations, look at what Kenya News Agency documented in 2024: seven members of one family died in a crash along the Mombasa–Nairobi highway—Francis Macharia (61), Irene Wang’ombe (37), Joyce Wairimu, Lemmy Macharia (12), Esther Nyambura (12), Esther Wanjiru (10), and Joyce Muthoni (8). One family, seven graves, and a country that moved on the next day.

And in late 2025, another family disaster unfolded at Kijabe: seven of nine members of a Kakamega family died in one accident, with relatives describing the shock of “all these graves” appearing at once. That is what road lawlessness looks like when it finishes its work—compounds turned into cemeteries, children’s laughter replaced by silence.

So let us speak plainly: when a driver knowingly speeds, overlaps, or overtakes dangerously—when a PSV crew overloads and rushes—when a truck is allowed onto the road with mechanical issues—when an officer accepts a bribe and releases a threat back to the highway—this is not “an accident.” It is preventable killing enabled by impunity.

This is where the hard debate comes in: should Kenya introduce capital punishment for traffic offences punishable by death—where conduct is so reckless, so repeated, so demonstrably dangerous, that it becomes equivalent to intentional disregard for human life? That is the question many grieving Kenyans are beginning to ask, not because they love harshness, but because they are tired of burying.

The argument for the harshest penalties is built on deterrence and moral clarity. If a society can attach the severest consequences to offences that predictably cause death, it sends a message that life is not cheap, that the road is not a gambling table, and that “nilikuwa na haraka” is not a defence to homicide.

The argument against capital punishment is equally serious: the justice system is not perfect, investigations can be compromised, and a corrupt enforcement environment can turn a death-penalty regime into a tool for extortion, scapegoating, or selective punishment. In a country where bribery is part of the road ecosystem, any irreversible penalty demands an exceptionally clean process.

But whichever side one takes, one point must be non-negotiable: Kenya’s current consequences are too weak for the scale of loss. When thousands die annually, when pedestrians are mowed down in record numbers, when repeat offenders return to the road like nothing happened, then the existing punishment architecture is failing the public.

If capital punishment is not adopted, then Kenya must still move to penalties that feel like the value of a life: long custodial sentences for fatal reckless driving, lifetime driving bans for repeat high-risk offenders, asset forfeiture where negligence is extreme, and mandatory imprisonment for officers and supervisors who facilitate the fraud that puts unqualified drivers on the road.

This is where the police must be named directly. Too many Kenyans experience traffic policing as negotiation, not enforcement. When an officer turns a deadly violation into “toa kitu kidogo,” that officer is not just corrupt—he is manufacturing funerals. The road becomes lawless because the law itself is sold at the roadside.

NTSA must also be named without politeness. If we can count deaths, we can also identify black spots, recurrent causes, and repeat offenders—and design enforcement and licensing reforms that actually bite. The public does not need more slogans. It needs a system that removes danger from the road quickly and permanently.

Read Also: Analyzing the Top 20 Leading Causes of Road Traffic Accidents Across 32 Countries

Driving schools must be audited like health facilities. A weak driving school is not a business problem; it is a public safety threat. If instructors are signing off incompetence, if candidates are being “coached” to pass a test instead of trained to drive responsibly, then the pipeline is producing killers with paperwork.

Boda boda culture needs honesty, not insults. Motorcycles are livelihoods, yes—but they have also become a frontier of disorder where helmets are optional, lanes are imaginary, and passenger safety is often an afterthought. The answer is not blanket demonisation; it is strict training, registration discipline, enforcement, and real penalties for repeat offenders—because “hustle” cannot be an excuse for endangering lives.

The commercial transport sector—matatus, buses, trucks—must stop behaving like time and profit are worth more than passengers. Speed governors, rest hours, vehicle inspections, and crew accountability cannot be “documents.” They must be enforced realities. If a vehicle is unsafe, it should not move—full stop.

And yes, the Cabinet Secretaries must be called out. The CS for Transport cannot be a ribbon-cutter who appears during tragedies to speak condolences, then disappears into the next press conference. The CS for Interior cannot supervise a policing system that treats enforcement like bargaining and then act surprised when bodies pile up. Leadership must be measured in reduced funerals, not speeches.

Kenya must also confront the truth that some roads are engineered for death: narrow stretches, poor signage, bad markings, chaotic merging, unprotected pedestrian crossings, and black spots that are “known” but left untreated for years. When a black spot remains a black spot, that is not negligence—it is policy violence.

Yet even perfect roads will not save a country that worships impatience.

We must admit a cultural sickness: the belief that being aggressive on the road is intelligence, that bullying your way through traffic is competence, that laws are for the weak. That mindset is killing us, and it is being taught by example—from adults to youth—every single day.

The way forward begins with a decision: do we treat road deaths like a national disaster or like background noise? If it is a disaster, then enforcement must become consistent and unbribable, licensing must become strict and verifiable, and courts must treat fatal reckless driving as a grave crime with grave consequences.

It also means building a chain of accountability that does not end with the driver. If a PSV owner pressures crews to speed, that owner should be liable. If a company loads a truck illegally or skips maintenance, that company should face criminal consequences. If an officer enables fraud, that officer should face prosecution, not transfer.

On the capital punishment debate specifically, Kenya must not pretend there is a simple answer. But we also must not hide behind complexity while people die. If we are not ready to attach the maximum penalty, then we must at least attach maximum certainty: swift investigations, strong evidence standards, fast prosecutions, and sentences that actually deter.

Because the current reality is an insult to every grieving parent: a child dies, the country trends for a day, and the same behaviours continue the next morning. Meanwhile, the bereaved carry the permanent sentence—empty seats at home, school shoes that will never be worn again, birthdays that will never be celebrated.

The moral test of a nation is whether it protects life when it is inconvenient and expensive. Road safety requires money, discipline, enforcement, and political courage. But the cost of inaction is higher: thousands dead yearly, tens of thousands injured, and families financially ruined by hospital bills, disability, and funeral expenses.

Kenya does not lack intelligence. Kenya lacks seriousness. We have allowed corruption, impatience, and weak punishment to create a permission slip for killing. If we want different outcomes, we must raise the price of lawlessness until it becomes irrational to break the rules.

Let this be the line we draw: no more bargaining with death. No more turning road crimes into small talk. No more burying children because adults refused to obey basic rules. Whether through the harshest penalties or through uncompromising enforcement and long imprisonment, Kenya must make one promise—and keep it: the road will no longer be a place where human life is discounted.

Read Also: Road Accidents Have Killed 3,609 Kenyans Since January

About Steve Biko Wafula

Steve Biko is the CEO OF Soko Directory and the founder of Hidalgo Group of Companies. Steve is currently developing his career in law, finance, entrepreneurship and digital consultancy; and has been implementing consultancy assignments for client organizations comprising of trainings besides capacity building in entrepreneurial matters.He can be reached on: +254 20 510 1124 or Email: info@sokodirectory.com

- January 2026 (138)

- January 2025 (119)

- February 2025 (191)

- March 2025 (212)

- April 2025 (193)

- May 2025 (161)

- June 2025 (157)

- July 2025 (227)

- August 2025 (211)

- September 2025 (270)

- October 2025 (297)

- November 2025 (230)

- December 2025 (219)

- January 2024 (238)

- February 2024 (227)

- March 2024 (190)

- April 2024 (133)

- May 2024 (157)

- June 2024 (145)

- July 2024 (136)

- August 2024 (154)

- September 2024 (212)

- October 2024 (255)

- November 2024 (196)

- December 2024 (143)

- January 2023 (182)

- February 2023 (203)

- March 2023 (322)

- April 2023 (297)

- May 2023 (267)

- June 2023 (214)

- July 2023 (212)

- August 2023 (257)

- September 2023 (237)

- October 2023 (264)

- November 2023 (286)

- December 2023 (177)

- January 2022 (293)

- February 2022 (329)

- March 2022 (358)

- April 2022 (292)

- May 2022 (271)

- June 2022 (232)

- July 2022 (278)

- August 2022 (253)

- September 2022 (246)

- October 2022 (196)

- November 2022 (232)

- December 2022 (167)

- January 2021 (182)

- February 2021 (227)

- March 2021 (325)

- April 2021 (259)

- May 2021 (285)

- June 2021 (272)

- July 2021 (277)

- August 2021 (232)

- September 2021 (271)

- October 2021 (304)

- November 2021 (364)

- December 2021 (249)

- January 2020 (272)

- February 2020 (310)

- March 2020 (390)

- April 2020 (321)

- May 2020 (335)

- June 2020 (327)

- July 2020 (333)

- August 2020 (276)

- September 2020 (214)

- October 2020 (233)

- November 2020 (242)

- December 2020 (187)

- January 2019 (251)

- February 2019 (215)

- March 2019 (283)

- April 2019 (254)

- May 2019 (269)

- June 2019 (249)

- July 2019 (335)

- August 2019 (293)

- September 2019 (306)

- October 2019 (313)

- November 2019 (362)

- December 2019 (318)

- January 2018 (291)

- February 2018 (213)

- March 2018 (275)

- April 2018 (223)

- May 2018 (235)

- June 2018 (176)

- July 2018 (256)

- August 2018 (247)

- September 2018 (255)

- October 2018 (282)

- November 2018 (282)

- December 2018 (184)

- January 2017 (183)

- February 2017 (194)

- March 2017 (207)

- April 2017 (104)

- May 2017 (169)

- June 2017 (205)

- July 2017 (189)

- August 2017 (195)

- September 2017 (186)

- October 2017 (235)

- November 2017 (253)

- December 2017 (266)

- January 2016 (164)

- February 2016 (165)

- March 2016 (189)

- April 2016 (143)

- May 2016 (245)

- June 2016 (182)

- July 2016 (271)

- August 2016 (247)

- September 2016 (233)

- October 2016 (191)

- November 2016 (243)

- December 2016 (153)

- January 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (4)

- March 2015 (164)

- April 2015 (107)

- May 2015 (116)

- June 2015 (119)

- July 2015 (145)

- August 2015 (157)

- September 2015 (186)

- October 2015 (169)

- November 2015 (173)

- December 2015 (205)

- March 2014 (2)

- March 2013 (10)

- June 2013 (1)

- March 2012 (7)

- April 2012 (15)

- May 2012 (1)

- July 2012 (1)

- August 2012 (4)

- October 2012 (2)

- November 2012 (2)

- December 2012 (1)