The Death of Grassroots Banking: How Kenya’s Microfinance Revolution Was Killed by Greed, Neglect, and Policy Failure

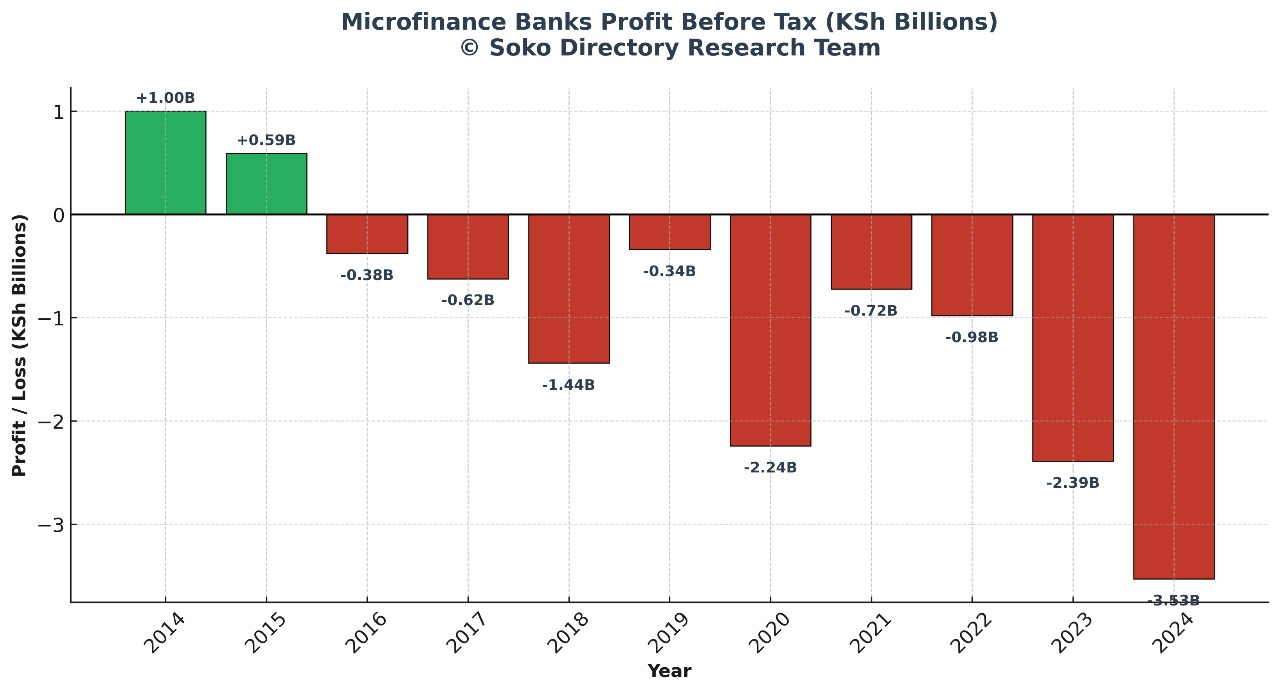

For nine consecutive years, Kenya’s microfinance banks have recorded losses. What was once a vibrant promise to uplift the unbanked now reads like an obituary of misplaced ambition and institutional betrayal. According to CBK data, the sector posted a staggering KSh 3.53 billion loss in 2024, marking the ninth straight year in the red. Only 4 out of 14 licensed microfinance banks made any profit, while three players — KWFT, Faulu, and SMEP — accounted for 88% of total losses.

This isn’t just a bad year. It’s a chronic illness eating away at the very foundation of Kenya’s financial inclusion story. The decline has been steady, unrelenting, and tragic. From a KSh 1 billion profit in 2014 to KSh 592 million in 2015, the fall began in 2016 and has never stopped. Each subsequent year deepened the hole: -377M in 2016, -622M in 2017, -1.44B in 2018, -2.24B in 2020, -2.39B in 2023, and now -3.53B in 2024. The trend is more than alarming — it’s a mirror reflecting systemic rot.

Microfinance banks were built on a noble idea — to democratize access to credit and savings for Kenya’s informal economy. The mama mboga, the boda boda rider, the market artisan — these were their customers. Yet the model that once gave voice to the voiceless has now become a victim of the very capitalism it sought to humanize. As commercial banks digitized, adapted, and ate into microfinance markets, the smaller institutions remained trapped in outdated systems and heavy overheads.

Default rates have exploded. Many microfinance banks lent aggressively during the pandemic, betting on a quick recovery, only to be hit by inflation, tax hikes, and dwindling household incomes. The cost-of-living crisis crushed repayment discipline. Deposits shrank. Borrowers disappeared. And as CBK tightened capital requirements and compliance costs rose, survival became a luxury only a few could afford.

Read Also: Eastleigh Traders Eye Sustainability and Longer Banking Hours

KWFT, once celebrated as the face of women’s empowerment, now bleeds at KSh 1.64 billion loss. Faulu, a pioneer of group lending, posted KSh 1.04 billion in losses. SMEP lost KSh 409 million. The survivors — Choice Bank, Caritas, and Sumac — barely broke even, posting small profits of KSh 66 million, KSh 50 million, and KSh 5 million, respectively. This isn’t a competition. It’s corporate triage.

The sector’s woes aren’t entirely self-inflicted. Policy indifference has been deadly. Kenya’s financial regulators have allowed a wild west where digital lenders, commercial banks, and SACCOs all cannibalize the same base without coordinated oversight. Instead of nurturing microfinance, the state has glorified fintech — turning the promise of financial inclusion into a predatory lending ecosystem dominated by apps, data exploitation, and usurious interest rates.

Meanwhile, some MFBs are selling their loan books to commercial banks just to stay solvent. Others are downsizing branches, shedding staff, or quietly pivoting into agency banking to survive under the umbrella of bigger lenders. What began as empowerment has turned into dependency.

The tragedy deepens when you remember the social purpose behind microfinance. These were not institutions meant to compete with Equity or KCB. They were supposed to bridge the gap left by them. They were to serve those without collateral, without pay slips, without digital footprints. Yet, by failing to innovate, by failing to digitize responsibly, and by clinging to donor-era bureaucracy, they’ve become irrelevant in a world moving at fintech speed.

Even CBK’s interventions seem too little, too late. The Microfinance (Deposit Taking) Regulations of 2008 have barely evolved to reflect today’s realities. New entrants face prohibitive licensing fees, outdated compliance frameworks, and little incentive to innovate. At the same time, CBK’s prudential guidelines continue to treat microfinance like mini commercial banks — a mismatch that crushes agility and spirit.

Critically, the government’s economic direction has also been unfriendly. Policies that favor big capital, tax incentives skewed toward foreign investors, and slow disbursement of SME support funds have all compounded the misery. The Hustler Fund, instead of empowering microfinance institutions, bypassed them entirely — a political shortcut that stripped the sector of millions in potential liquidity and relationships.

When grassroots banking dies, financial democracy dies with it. Every closure or downsizing of a microfinance bank means thousands of informal traders losing access to credit, thousands of women cut off from growth capital, and countless rural communities sliding back into cash economies. It’s a quiet crisis, invisible to the urban elite but devastating to the nation’s economic backbone.

This isn’t just an accounting problem. It’s a national development problem. Kenya cannot achieve inclusive growth when its financial system systematically excludes those who need it most. The collapse of microfinance banks is not just their failure — it’s a policy failure, a leadership failure, and a moral failure.

The irony is that, as microfinance bleeds, the very big banks that ignored the poor for decades now market “micro” products digitally — without human touch, without empathy, and without community reinvestment. The very spirit of microfinance — relationship-based trust — has been replaced by algorithmic coldness.

If nothing changes, 2025 may mark the year the microfinance model officially dies in Kenya. Unless CBK intervenes with reform — merging smaller players, creating a microfinance stability fund, and incentivizing rural digitization — the sector will continue to shrink until it becomes a footnote in Kenya’s economic history.

It’s time for the government, regulators, and financial sector to have an honest conversation: do we still believe in financial inclusion, or are we comfortable watching capitalism eat its own children?

Because behind every number in that red bar is a broken dream, a closed kiosk, and a family that believed in the promise of microfinance.

Read Also: Top 5 Things You Can Do With The KCB Mobile Banking App

About Steve Biko Wafula

Steve Biko is the CEO OF Soko Directory and the founder of Hidalgo Group of Companies. Steve is currently developing his career in law, finance, entrepreneurship and digital consultancy; and has been implementing consultancy assignments for client organizations comprising of trainings besides capacity building in entrepreneurial matters.He can be reached on: +254 20 510 1124 or Email: info@sokodirectory.com

- January 2025 (119)

- February 2025 (191)

- March 2025 (212)

- April 2025 (193)

- May 2025 (161)

- June 2025 (157)

- July 2025 (226)

- August 2025 (211)

- September 2025 (270)

- October 2025 (65)

- January 2024 (238)

- February 2024 (227)

- March 2024 (190)

- April 2024 (133)

- May 2024 (157)

- June 2024 (145)

- July 2024 (136)

- August 2024 (154)

- September 2024 (212)

- October 2024 (255)

- November 2024 (196)

- December 2024 (143)

- January 2023 (182)

- February 2023 (203)

- March 2023 (322)

- April 2023 (297)

- May 2023 (267)

- June 2023 (214)

- July 2023 (212)

- August 2023 (257)

- September 2023 (237)

- October 2023 (264)

- November 2023 (286)

- December 2023 (177)

- January 2022 (293)

- February 2022 (329)

- March 2022 (358)

- April 2022 (292)

- May 2022 (271)

- June 2022 (232)

- July 2022 (278)

- August 2022 (253)

- September 2022 (246)

- October 2022 (196)

- November 2022 (232)

- December 2022 (167)

- January 2021 (182)

- February 2021 (227)

- March 2021 (325)

- April 2021 (259)

- May 2021 (285)

- June 2021 (272)

- July 2021 (277)

- August 2021 (232)

- September 2021 (271)

- October 2021 (304)

- November 2021 (364)

- December 2021 (249)

- January 2020 (272)

- February 2020 (310)

- March 2020 (390)

- April 2020 (321)

- May 2020 (335)

- June 2020 (327)

- July 2020 (333)

- August 2020 (276)

- September 2020 (214)

- October 2020 (233)

- November 2020 (242)

- December 2020 (187)

- January 2019 (251)

- February 2019 (215)

- March 2019 (283)

- April 2019 (254)

- May 2019 (269)

- June 2019 (249)

- July 2019 (335)

- August 2019 (293)

- September 2019 (306)

- October 2019 (313)

- November 2019 (362)

- December 2019 (318)

- January 2018 (291)

- February 2018 (213)

- March 2018 (275)

- April 2018 (223)

- May 2018 (235)

- June 2018 (176)

- July 2018 (256)

- August 2018 (247)

- September 2018 (255)

- October 2018 (282)

- November 2018 (282)

- December 2018 (184)

- January 2017 (183)

- February 2017 (194)

- March 2017 (207)

- April 2017 (104)

- May 2017 (169)

- June 2017 (205)

- July 2017 (189)

- August 2017 (195)

- September 2017 (186)

- October 2017 (235)

- November 2017 (253)

- December 2017 (266)

- January 2016 (164)

- February 2016 (165)

- March 2016 (189)

- April 2016 (143)

- May 2016 (245)

- June 2016 (182)

- July 2016 (271)

- August 2016 (247)

- September 2016 (233)

- October 2016 (191)

- November 2016 (243)

- December 2016 (153)

- January 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (4)

- March 2015 (164)

- April 2015 (107)

- May 2015 (116)

- June 2015 (119)

- July 2015 (145)

- August 2015 (157)

- September 2015 (186)

- October 2015 (169)

- November 2015 (173)

- December 2015 (205)

- March 2014 (2)

- March 2013 (10)

- June 2013 (1)

- March 2012 (7)

- April 2012 (15)

- May 2012 (1)

- July 2012 (1)

- August 2012 (4)

- October 2012 (2)

- November 2012 (2)

- December 2012 (1)