It Is Time To Aggressively Protect Arable Land In Kenya If We Are To Protect Our Food Security

In the heart of East Africa, the reality of arable land disappearing under urban sprawl and informal settlement is beginning to cripple more than just the soil—it is slowly starving the nation’s future. In Kenya, agriculture contributes approximately 22.4 % of gross domestic product and employs over 60 % of the workforce, yet less than 20 % of the land is classified as high-potential agricultural terrain. This imbalance is not by accident: it is the product of decades of land-use policy neglect, rapid population growth, and uncoordinated development that treats arable land and vital “water tower” regions as disposable real estate. The consequences ripple through food systems, poverty metrics, and national sovereignty.

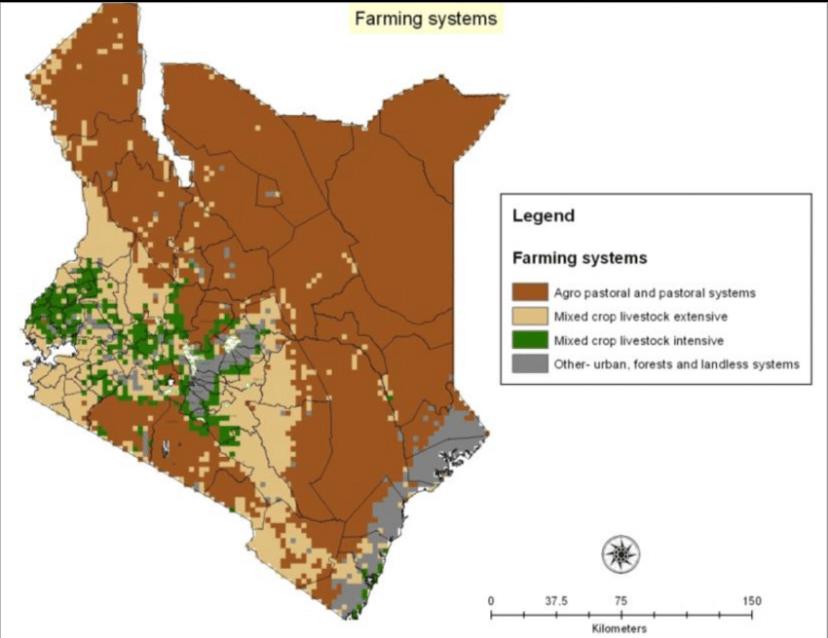

The arithmetic is stark. While national cereal imports grow, yields stagnate. The farming high-rainfall zone—roughly 10 % of Kenya’s arable land—produces about 70 % of the country’s commercial agricultural output. Yet overall productivity remains low due to fragmented land parcels, smallholder constraints, inadequate mechanisation, and loss of fertile ground to real-estate conversion. Meanwhile, the population continues its upward climb, pressuring the margins of arable land and reducing per-capita soil availability. According to one land-use change study, only about 20 % of Kenya’s land is arable, and the five major water-tower regions fall within this arable belt, while roughly 75 % of the population clusters there.

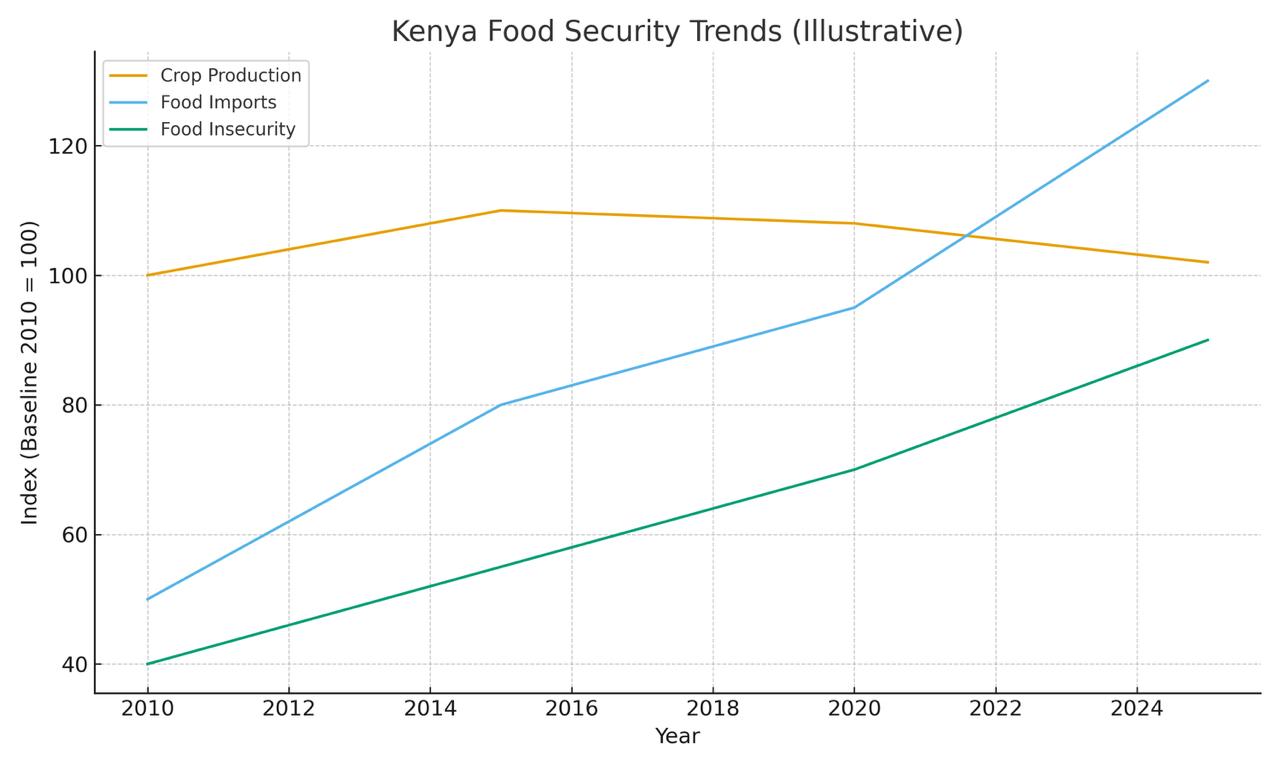

One key diagram illustrates this destructive tension: as land becomes available for large-scale, high-yield agriculture contracts, and as development encroaches on water-tower ecosystems, food security deteriorates. Estimates show that in sample agrarian zones, only 22.6 % of households were food secure, while 39.5 % experienced severe food insecurity. These are not isolated statistics but symptomatic of a deeper structural failure—one in which arable soil is treated as expendable, rather than indispensable.

Efforts to boost agriculture through irrigation and productivity gains are welcome—but they cannot compensate for the rapid destruction of the very land that underpins food sovereignty. Kenya’s water-resource profile shows that 75 % of surface water originates from a handful of catchments in the central highlands and the west. When those catchments are compromised by land-use change, deforestation, and building, the impact is twofold: reduced water availability for irrigation and downstream households, and degraded ecosystem resilience precisely when climate variation is intensifying.

Consider the poverty dimension: agriculture remains the mainstay for the bulk of Kenya’s poor. According to FAO and national data, the agrarian sector provides 75 % of raw materials for industry, 25 % of GDP, and employs 70 % of labour in some rural zones. Yet as arable land declines, the capacity of rural households to participate in viable farming diminishes, increasing vulnerability to shocks and heightening reliance on food imports or urban-migration coping strategies.

Import dependency is rising. Projections suggest that if current trends hold, the gap between agricultural production and consumption will widen dramatically. One estimate indicated that by 2040, Kenya might need to import more than 20 million metric tonnes of agricultural goods—or roughly 25 % of demand. This looming import burden is not simply an economic cost but a national security vulnerability, exposing Kenya to global price shocks, supply chain disruption, and climate-driven volatility.

Read Also: William Ruto To Pay Content Creators Promoting Housing, Health, Jobs, and Agriculture

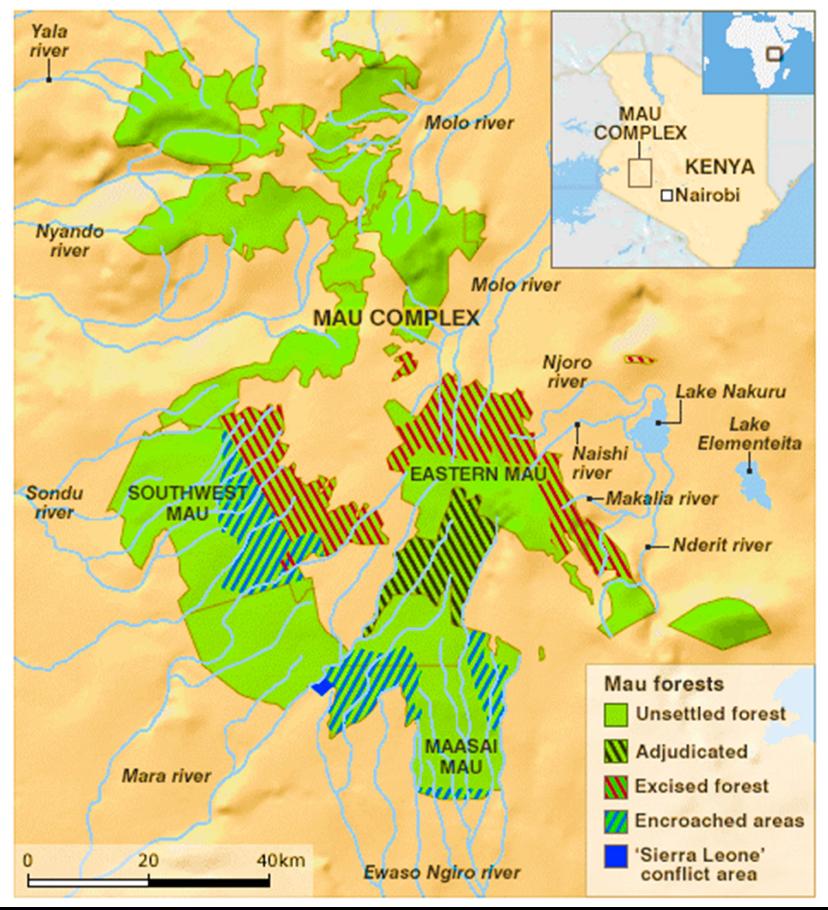

The conversion of arable land into buildings, infrastructure, and speculative real estate is often done without accounting for long-term societal cost. In prime high-potential zones and forest-rich water-catchment sites, land parcels are fragmented, sold for subdivisions and emergent housing—often bypassing strategic agricultural zoning. Without legal prohibition of building on prime arable land and water-tower catchments, the logic of short-term gain overrides generational food security. One recent national audit of water-tower conservation exposed significant neglect and encroachment.

Food security is intrinsically linked to land tenure and an enabling policy environment. But in Kenya, land tenure complexity, informal settlement proliferation, and weak enforcement of zoning regulations have allowed arable land to erode. The 2024–25 Agriculture Census aims to capture more comprehensive data, but action must follow data. We cannot wait while the acreage of high-yield land shrinks; the tide of development must be channelled so that soil and water remain priority assets for the nation, not secondary to the speculative value of land.

Fragmentation of smallholder plots is another symptom of the bigger disease. Research shows that the average parcel size is shrinking, which undermines mechanisation and economies of scale, and reduces yields. When high-potential land is subdivided and built on, productivity falls, and acclimatised ecosystems lose resilience. The aggregate effect is slower growth in agricultural output, rising food imports, and increased risk of household hunger.

Moreover, the climate risk overlay cannot be ignored. Kenya’s arable highlands and water-tower regions provide critical buffering against drought and erratic rains. But when land cover is damaged—through building, deforestation, or encroachment—the capacity of those landscapes to regulate runoff, retain soil moisture, and sustain irrigation networks is weakened. In effect, land-use mismanagement becomes a multiplier of climate shock. One study emphasised that land-cover change in and around water towers is a direct threat to the ecosystem services they deliver.

Food insecurity remains entrenched. Household surveys show that age-dependency ratios in Kenya remain high—with the 2015/16 survey indicating an 84 ratio per 100 working persons—thereby reducing the resilience of households to absorb income shocks and food price inflation. When agricultural productivity is threatened by land loss, these demographic pressures become more acute, especially in rural settings where non-farm employment is limited.

In agribusiness terms, Kenya’s high-potential areas produce most of the commercial output. Semi-arid and arid zones account for about 20 % and 10 % of output, respectively, despite occupying vast land areas. Thus, the high-productivity zones are both economically critical and under existential threat from land conversion. To neglect them is to neglect the majority of the nation’s agricultural backbone.

By failing to prioritise land protection, Kenya risks a future where urban build-up, speculative real estate, and infrastructure expansion eat the farmland and sources of water that once sustained it. The value equation must shift: soil, water, and food sovereignty should outrank short-term land appreciation. Protecting the five major water-tower regions is especially urgent—these catchments generate the bulk of Kenya’s surface water and underpin both agriculture and urban water supply.

For instance, the Mau Forest Complex alone has experienced rising population spill-over and land-use change that threaten its hydrological function. If upstream catchment land is developed recklessly, downstream agricultural zones lose irrigation potential and natural buffering against drought. The ripple effect extends from farm to city to national export potential.

Conceptually, this is not purely a rural problem. Urban food security is also dependent on stable rural supply chains. When farmland disappears, urban residents face higher food prices or greater reliance on imports. That in turn impacts the cost of living, inflation, and ultimately social stability. The systemic nature of land loss means that its consequences pervade the economy, the food system, and even geopolitics.

Taking a longer view, the ratio of arable land to population is trending unfavourably. According to World Bank data, Kenya’s arable land (percentage of land area) is finite and under pressure. Without curbing the loss of high-potential farmland, the nation will face an even steeper climb to meet its commitments to the Sustainable Development Goal 2 (zero hunger), the Sustainable Development Goal 12 (responsible production), and the Sustainable Development Goal 15 (life on land).

The phenomenon of idle land also merits attention. As urbanisation expands, prime land near water towers or fertile zones often lies idle pending development or sale, yet remains outside agriculture. Such inertia further reduces effective food-production capacity. Concurrently, smallholders often lack access to irrigation—only a small fraction of arable land is equipped for irrigation—and thus remain vulnerable.

The policy vacuum is glaring. Kenya’s Food Systems and Land Use Action Plan (2023) recognises agriculture’s centrality but also acknowledges that land-use regulation, soil protection, and water tower conservation must be addressed to achieve food security. Yet without a statutory prohibition on building on prime agricultural and water-tower land, the plan remains aspirational. The legal architecture must elevate soil and water as ecological rights, not merely economic-development trade-offs.

While numerical precision is limited, the trend is unambiguous: as domestic production stagnates and arable land shrinks, imports and the number of food-insecure households rise. Empirical studies confirm that roughly 39.5 % of households in certain zones report severe food insecurity.

The moral dimension cannot be ignored: when arable land is converted to speculative estate, the poorest bear the cost while the speculative gain accrues to a small elite. This deepens rural poverty, weakens agribusiness viability, and deprives future generations of food sovereignty. In Kenya, smallholder farmers supply 65 % of the marketed agricultural produce. The land they farm is non-renewable in practical human time scales. It must be guarded.

A lethal intersection arises between land conversion and food-price inflation. Eventual loss of farmland means fewer production bases; as supply tightens, staple-food prices increase. Kenya’s dependence on maize imports and other staples makes it vulnerable. When drought hits or supply chains falter, households with already high age-dependency ratios suffer. Food becomes a security issue, not just an economic one.

It is naïve to assume that urbanisation and housing development must always override agricultural land. In a country where nearly three-quarters of surface water begins in highland zones that overlap with arable land, the choice is between unsound development and sustainable survival. If these highland zones lose their buffering capacity, the costs are enormous: lower yields, increased drought exposure, degraded infrastructure, and higher water and food costs.

Ultimately, the battle is one of priorities. If Kenya treats arable land as a short-term asset for sale, rather than a long-term asset for feeding the nation, the inevitable outcome is a shrinkage of agriculture’s contribution to the economy, lower export earnings, increased vulnerability to external supply shocks, and rising poverty. The trade-off is real, and this article lays that trade-off bare.

The narrative that development must mean more buildings must change. In rural zones, farmland represents more than plots—it is the foundation of livelihoods, nutrition, and resilience. In the cattlement of the highland “water towers”, land-cover integrity is as important as the square meter of housing erected. These watershed zones generate the water for irrigation, hydro-power, and domestic consumption alike.

Projecting forward, if Kenya were to continue on the current trajectory—erosion of arable land, stagnant yields, increased population, and intensifying climate risk—the food-import bill will balloon, rural households will face intensifying hunger, and the agribusiness sector will bear the brunt. Rural poverty will not be reduced by building houses on former farmland; it will be aggravated.

Resource-rich as Kenya is, the core risk lies not in a lack of land, but in the misuse of the land that is available. Land-cover change studies indicate that agriculture is the principal driver of land-use change in tropical regions—but in Kenya, the reverse is happening: non-agricultural development encroaches on agricultural zones. The result is loss of soil fertility, fragmented parcels, weaker farming systems, and rising food insecurity.

Seen through the lens of agribusiness, protecting arable land is not an ideological whim—it is a commercial imperative. Numerous studies show that value addition in agriculture in Kenya remains constrained because primary production remains the bottleneck. Land loss further squeezes that bottleneck. If agribusiness is to thrive—if the downstream processing, exports, employment, and value chains are to expand—the upstream input of land must be secured.

From a poverty-alleviation viewpoint, safeguarding farmland and water-tower catchments becomes an inclusive growth strategy. Smallholder farmers, who are often women and youth, rely on land and water that is vulnerable to urbanisation. When land is lost, their agency is undermined, and inequality deepens. Food insecurity then becomes a rural–urban bridge of suffering, not just a countryside issue.

To summarise the stakes: one parcel of high-potential farmland sold for speculative profit represents more than money—it represents lost tonnes of maize, lost employment, lost ecosystem services, lost resilience. When the cumulative effect is multiplied across thousands of parcels, the national effect is catastrophic.

Kenya already faces multiple stresses: climate change, water scarcity (“the Falkenmark Index” for Kenya in 2017 was 618 m³/year per capita, versus a Sub-Saharan median of 2,519), agricultural yields stuck in low gear, and rural youth unemployment. Against that context, protecting the land that can yield food, water, and jobs is both commonsense and strategic.

In closing, the outcome is simple but profound: safeguarding arable land and vital water-tower regions is not optional—it is fundamental to food security, poverty reduction, agribusiness advancement, and national sovereignty. The maths and the maps underscore this: once the soil and water go, the nation bleeds.

- January 2025 (119)

- February 2025 (191)

- March 2025 (212)

- April 2025 (193)

- May 2025 (161)

- June 2025 (157)

- July 2025 (226)

- August 2025 (211)

- September 2025 (270)

- October 2025 (297)

- November 2025 (155)

- January 2024 (238)

- February 2024 (227)

- March 2024 (190)

- April 2024 (133)

- May 2024 (157)

- June 2024 (145)

- July 2024 (136)

- August 2024 (154)

- September 2024 (212)

- October 2024 (255)

- November 2024 (196)

- December 2024 (143)

- January 2023 (182)

- February 2023 (203)

- March 2023 (322)

- April 2023 (297)

- May 2023 (267)

- June 2023 (214)

- July 2023 (212)

- August 2023 (257)

- September 2023 (237)

- October 2023 (264)

- November 2023 (286)

- December 2023 (177)

- January 2022 (293)

- February 2022 (329)

- March 2022 (358)

- April 2022 (292)

- May 2022 (271)

- June 2022 (232)

- July 2022 (278)

- August 2022 (253)

- September 2022 (246)

- October 2022 (196)

- November 2022 (232)

- December 2022 (167)

- January 2021 (182)

- February 2021 (227)

- March 2021 (325)

- April 2021 (259)

- May 2021 (285)

- June 2021 (272)

- July 2021 (277)

- August 2021 (232)

- September 2021 (271)

- October 2021 (304)

- November 2021 (364)

- December 2021 (249)

- January 2020 (272)

- February 2020 (310)

- March 2020 (390)

- April 2020 (321)

- May 2020 (335)

- June 2020 (327)

- July 2020 (333)

- August 2020 (276)

- September 2020 (214)

- October 2020 (233)

- November 2020 (242)

- December 2020 (187)

- January 2019 (251)

- February 2019 (215)

- March 2019 (283)

- April 2019 (254)

- May 2019 (269)

- June 2019 (249)

- July 2019 (335)

- August 2019 (293)

- September 2019 (306)

- October 2019 (313)

- November 2019 (362)

- December 2019 (318)

- January 2018 (291)

- February 2018 (213)

- March 2018 (275)

- April 2018 (223)

- May 2018 (235)

- June 2018 (176)

- July 2018 (256)

- August 2018 (247)

- September 2018 (255)

- October 2018 (282)

- November 2018 (282)

- December 2018 (184)

- January 2017 (183)

- February 2017 (194)

- March 2017 (207)

- April 2017 (104)

- May 2017 (169)

- June 2017 (205)

- July 2017 (189)

- August 2017 (195)

- September 2017 (186)

- October 2017 (235)

- November 2017 (253)

- December 2017 (266)

- January 2016 (164)

- February 2016 (165)

- March 2016 (189)

- April 2016 (143)

- May 2016 (245)

- June 2016 (182)

- July 2016 (271)

- August 2016 (247)

- September 2016 (233)

- October 2016 (191)

- November 2016 (243)

- December 2016 (153)

- January 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (4)

- March 2015 (164)

- April 2015 (107)

- May 2015 (116)

- June 2015 (119)

- July 2015 (145)

- August 2015 (157)

- September 2015 (186)

- October 2015 (169)

- November 2015 (173)

- December 2015 (205)

- March 2014 (2)

- March 2013 (10)

- June 2013 (1)

- March 2012 (7)

- April 2012 (15)

- May 2012 (1)

- July 2012 (1)

- August 2012 (4)

- October 2012 (2)

- November 2012 (2)

- December 2012 (1)