East Africa Faces Uneven Rains As Food Security Is Threatened

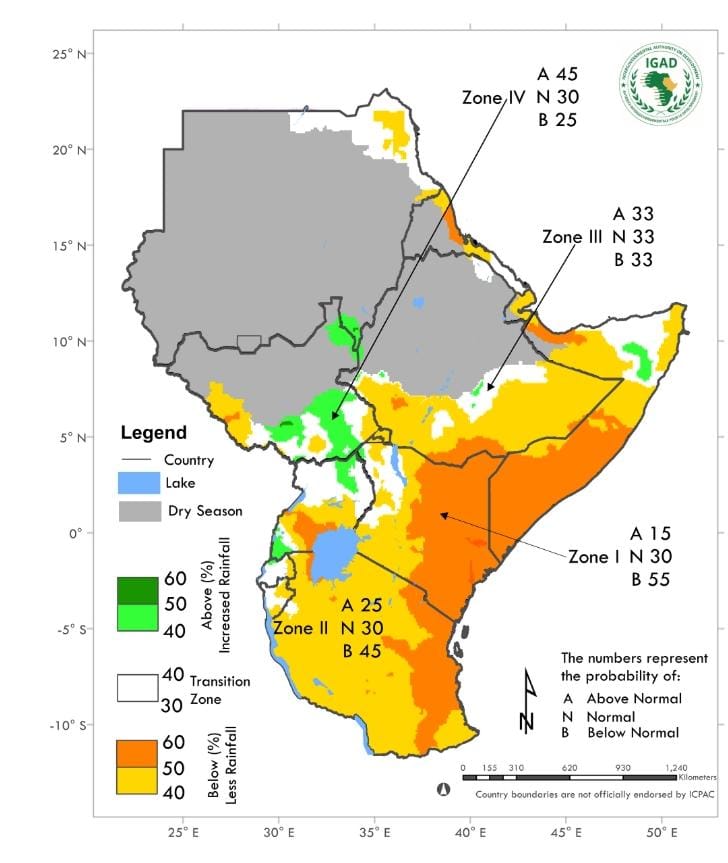

East Africa is heading into a season of uneven rainfall patterns that could reshape food security, energy generation, and cross-border trade. The latest forecast from IGAD’s Climate Prediction and Applications Centre (ICPAC) shows a patchwork of excess rains, prolonged dryness, and transition zones that will leave governments juggling between bumper harvests in some regions and looming droughts in others.

At the core of the forecast lies a split reality. Western Kenya, northern Uganda, and parts of southern Sudan are projected to receive above-normal rainfall (40–60% probability). These zones are shaded in green on the map, signaling potential relief for farmers who depend on rain-fed agriculture. For Kenya, this could mean stronger yields in maize-producing counties like Bungoma, Kakamega, and Trans Nzoia, helping offset food inflation that has plagued households since 2022.

But the optimism quickly fades as one moves eastward. The vast swathes of Kenya’s arid and semi-arid lands—stretching from Turkana and Marsabit through Isiolo to northern Kitui and Garissa—are colored orange, marking below-normal rainfall with up to 60% probability. For pastoralist communities, this translates to a prolonged lean season, heightened conflict over pasture, and greater reliance on food aid. The “zone of dryness” aligns with some of the most fragile areas where livestock is both livelihood and currency.

Ethiopia presents an equally mixed outlook. The southern highlands may see moderate rains, but the Somali region and eastern corridor are expected to remain under significant water stress. This will likely worsen food insecurity in areas already grappling with high displacement, while raising tensions with Somalia over shared water resources.

Read Also: Tanzania Is The Rot Killing The East African Dream

Tanzania, meanwhile, is not immune. The central and coastal belt leans heavily toward below-normal rainfall, raising questions for the country’s hydro-dependent power sector. Reduced inflows into reservoirs like Mtera and Kidatu could force Tanzania Electric Supply Company (TANESCO) to ration power or turn back to costly thermal generation—risking higher energy tariffs and subdued industrial growth.

Uganda and South Sudan offer a more positive outlook, with higher-than-average rainfall promising better crop output. But heavy rains carry risks of their own—flooding in low-lying areas, destruction of infrastructure, and spikes in waterborne diseases. Already, analysts note that East Africa’s food production systems are highly vulnerable to climate volatility: a season of too much rain can be just as devastating as one with too little.

For Nairobi policymakers, the forecast complicates the government’s flagship Bottom-Up Economic Transformation Agenda. Agricultural revival hinges on stable rainfall, yet the climate map suggests patchwork outcomes. Western breadbasket regions could ease inflationary pressures, but drylands that supply Kenya’s livestock chain will continue to languish. With maize, wheat, and edible oil prices still exposed to global shocks, food security in Kenya will likely remain fragile well into 2025.

Water scarcity in arid Kenya also means heightened risk of conflict. Resource-based clashes in Turkana, Baringo, and Marsabit are expected to intensify, straining internal security and cross-border peace along Ethiopia and South Sudan’s frontiers. Donor agencies will be under pressure to expand humanitarian assistance, while Kenya’s Treasury faces competing demands from debt servicing and drought mitigation.

For investors, the weather outlook sends mixed signals. On one hand, strong rains in western Kenya and Uganda offer upside potential for agribusiness, fertilizer companies, and food processors. On the other, weaker rains in Kenya’s drylands and Tanzania’s energy corridor raise red flags for insurers, infrastructure financiers, and governments banking on steady agricultural tax revenues.

Climate unpredictability also sharpens the debate on green transition financing. East Africa’s reliance on hydropower makes rainfall forecasts not just agricultural indicators but also power market drivers. Drought-induced power shortages in Kenya and Tanzania could push policymakers to accelerate renewable diversification—solar, wind, and geothermal—where the region holds vast untapped potential.

But the political dimension cannot be ignored. In Kenya, where the government is already facing public anger over the cost of living, another season of uneven rainfall could inflame discontent. Food inflation has historically triggered political unrest in Nairobi. A bad harvest in the eastern and northeastern counties risks undermining national cohesion, especially if perceptions grow that some communities are left behind in drought response.

Ethiopia faces a similar test. With the government juggling post-conflict reconstruction and restive regions in Oromia and Tigray, the rainfall deficit in the Somali region could re-ignite grievances. Food insecurity has historically been a catalyst for instability in Addis Ababa’s periphery.

Therefore, IGAD’s forecast paints a picture of climate asymmetry. Winners and losers will emerge across borders: fertile west vs. dry east, smallholder farmers vs. pastoralists, food processors vs. energy utilities. The broader story is one of fragility—East Africa’s economies remain heavily hostage to the sky, with little insulation against climate volatility.

The next six months will test the region’s ability to adapt, finance resilience, and cushion vulnerable households. For Kenya, the rains may bring relief to the west, but for the arid north and east, the season could be another chapter in a long story of scarcity.

Read Also: Stanbic’s Joshua Oigara Appointed To Lead The Lender’s East African Region

- January 2026 (220)

- February 2026 (243)

- March 2026 (62)

- January 2025 (119)

- February 2025 (191)

- March 2025 (212)

- April 2025 (193)

- May 2025 (161)

- June 2025 (157)

- July 2025 (227)

- August 2025 (211)

- September 2025 (270)

- October 2025 (297)

- November 2025 (230)

- December 2025 (219)

- January 2024 (238)

- February 2024 (227)

- March 2024 (190)

- April 2024 (133)

- May 2024 (157)

- June 2024 (145)

- July 2024 (136)

- August 2024 (154)

- September 2024 (212)

- October 2024 (255)

- November 2024 (196)

- December 2024 (143)

- January 2023 (182)

- February 2023 (203)

- March 2023 (322)

- April 2023 (297)

- May 2023 (267)

- June 2023 (214)

- July 2023 (212)

- August 2023 (257)

- September 2023 (237)

- October 2023 (264)

- November 2023 (286)

- December 2023 (177)

- January 2022 (293)

- February 2022 (329)

- March 2022 (358)

- April 2022 (292)

- May 2022 (271)

- June 2022 (232)

- July 2022 (278)

- August 2022 (253)

- September 2022 (246)

- October 2022 (196)

- November 2022 (232)

- December 2022 (167)

- January 2021 (182)

- February 2021 (227)

- March 2021 (325)

- April 2021 (259)

- May 2021 (285)

- June 2021 (272)

- July 2021 (277)

- August 2021 (232)

- September 2021 (271)

- October 2021 (304)

- November 2021 (364)

- December 2021 (249)

- January 2020 (272)

- February 2020 (310)

- March 2020 (390)

- April 2020 (321)

- May 2020 (335)

- June 2020 (327)

- July 2020 (333)

- August 2020 (276)

- September 2020 (214)

- October 2020 (233)

- November 2020 (242)

- December 2020 (187)

- January 2019 (251)

- February 2019 (215)

- March 2019 (283)

- April 2019 (254)

- May 2019 (269)

- June 2019 (249)

- July 2019 (335)

- August 2019 (293)

- September 2019 (306)

- October 2019 (313)

- November 2019 (362)

- December 2019 (318)

- January 2018 (291)

- February 2018 (213)

- March 2018 (275)

- April 2018 (223)

- May 2018 (235)

- June 2018 (176)

- July 2018 (256)

- August 2018 (247)

- September 2018 (255)

- October 2018 (282)

- November 2018 (282)

- December 2018 (184)

- January 2017 (183)

- February 2017 (194)

- March 2017 (207)

- April 2017 (104)

- May 2017 (169)

- June 2017 (205)

- July 2017 (189)

- August 2017 (195)

- September 2017 (186)

- October 2017 (235)

- November 2017 (253)

- December 2017 (266)

- January 2016 (164)

- February 2016 (165)

- March 2016 (189)

- April 2016 (143)

- May 2016 (245)

- June 2016 (182)

- July 2016 (271)

- August 2016 (247)

- September 2016 (233)

- October 2016 (191)

- November 2016 (243)

- December 2016 (153)

- January 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (4)

- March 2015 (164)

- April 2015 (107)

- May 2015 (116)

- June 2015 (119)

- July 2015 (145)

- August 2015 (157)

- September 2015 (186)

- October 2015 (169)

- November 2015 (173)

- December 2015 (205)

- March 2014 (2)

- March 2013 (10)

- June 2013 (1)

- March 2012 (7)

- April 2012 (15)

- May 2012 (1)

- July 2012 (1)

- August 2012 (4)

- October 2012 (2)

- November 2012 (2)

- December 2012 (1)