Kenya’s Uneven Rains Threaten Food Security, Energy Stability And Fiscal Space

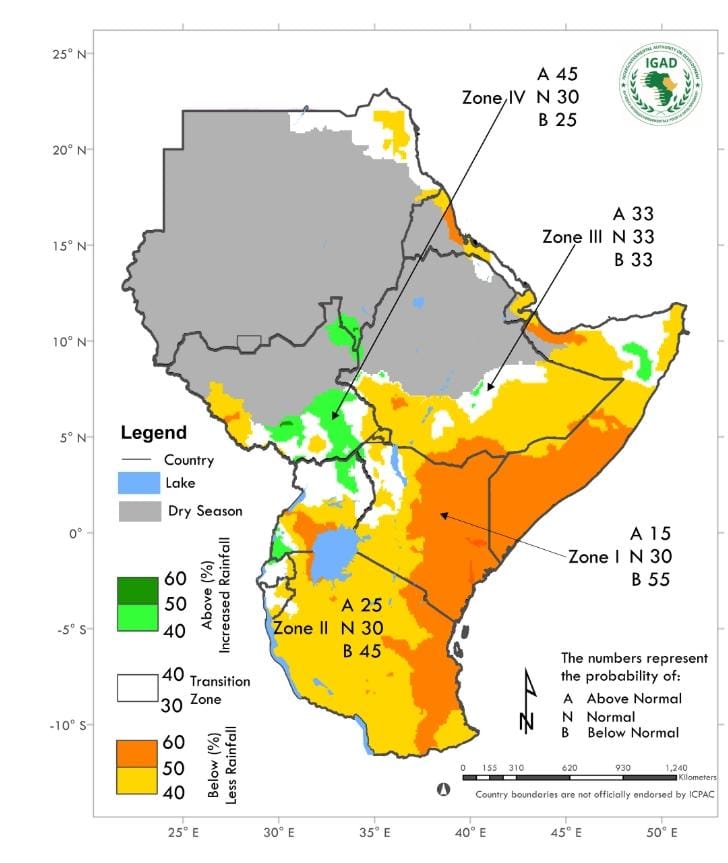

The seasonal outlook released at GHACOF71 by IGAD’s ICPAC shows a clear split: below-normal rainfall is the dominant signal across eastern Kenya and much of the country’s arid and semi-arid lands (ASALs), while pockets of western and highland Kenya have a higher chance of above-normal rains. That split is the single weather story that will shape Kenya’s food, fuel, power, and political economy over the coming months.

This is not a subtle risk. ICPAC’s OND (October–December) forecast explicitly flags an increased likelihood of below-average rains for eastern Kenya and the eastern Horn, while western corridors are more likely to receive wetter-than-normal conditions. For Kenyan policymakers and markets, that asymmetry matters: gains in the West will do little to replace losses in pastoral and marginal agricultural areas that are already food-insecure.

Start with the farmers. Western Kenya (counties such as Bungoma, Kakamega, and parts of Trans Nzoia and Vihiga) sits in the green on the ICPAC map — the best-case zone for cereal and cash-crop prospects. If the forecast verifies, expect improved short-season maize and vegetable yields in those counties, which could temporarily relieve local market pressure and help some processors and traders rebuild stocks. That said, national cereal balances depend heavily on multiple regions; strong rains in the west cannot fully offset failures in large producing or feeding zones.

Contrast that with the East. Turkana, Marsabit, Samburu, Isiolo, Garissa, Tana River, and parts of Kitui and Wajir are in the below-normal band. For pastoral communities whose livelihoods are overwhelmingly livestock-based, reduced rain means poorer pasture, lower milk production, malnourished herds, and higher mortality — the classic pathway from weak rains to humanitarian need. NDMA and FEWS NET have already signalled ongoing drought alerts and the likelihood of persistent stress in many ASAL counties.

Read Also: Kenya Met Warns Of Cold Nights, Rainfall In The Following Counties This Week

Livestock dynamics are the immediate economic effect to watch. In ASALs, weakened pasture and water scarcity will push herders to migrate longer distances, increasing conflict risk at water points and grazing corridors. The market implication: fewer animals mature for sale, supply to butchers and exporters tightens, and meat and live-animal prices may spike locally even as national average meat availability falls. FEWS NET’s recent messaging has consistently linked poor short rains to prolonged pastoral vulnerability.

Food prices are next-order. Kenya’s household food inflation remains sensitive to maize, wheat, and edible oil supply shocks. A short rain miss in key marginal cropping zones reduces planting and harvest prospects into early 2026, compressing market supplies and keeping downward pressure off inflation only where western surpluses arrive. For urban consumers in Nairobi and Mombasa — who rely on national distribution rather than local crops — price relief will be uneven and politically salient.

Humanitarian needs will climb without rapid, targeted responses. NDMA’s county early warning bulletins already show several counties in “alert” or worse, and national assessments warn of below-average short rains translating into below-average crop production in marginal areas. If the OND forecast verifies, the humanitarian caseload for food assistance and cash transfers is likely to rise in the late 2025–early 2026 window.

Electricity and energy markets must be watched closely. Kenya’s grid benefits from a diversified mix, including geothermal and hydro. Reservoirs such as Masinga and Kiambere have recently reported healthy levels, and hydropower output has held up in 2025—yet extended dry spells in catchment areas would reduce inflows and force higher reliance on thermal generation or expensive imports. Any sustained drop in hydropower contribution would push up generation costs, risk load-shedding, and squeeze government subsidies or household energy bills. KenGen and KPLC reporting earlier in 2025 showed stable reservoir levels, but the seasonal outlook raises a near-term downside risk to hydropower.

Agribusiness and fertilizer demand will be bifurcated. Input suppliers in western and high-potential maize belts could see stronger demand if farmers capitalize on above-normal rain signals. But in ASALs and marginal cropping areas, farmers will likely pull back on fertilizer and seed purchases, lowering demand and squeezing local agro-dealer margins. That volatility creates cash-flow pressures for rural microfinance portfolios concentrated in mixed agricultural counties.

On the fiscal front, the government will face trade-offs. NDMA, treasury planners, and county governments will need to juggle drought response, social safety nets (like HSNP in selected ASAL counties), and existing budget pressures from debt servicing. Expanded cash transfers and emergency procurement strain fiscal space and may force reallocations from capital projects — a politically delicate choice ahead of any election cycle. The NDMA’s existing safety-net programming footprint will likely expand if the forecast materializes.

Healthcare and nutrition: poor rains translate rapidly into reduced milk consumption and higher acute malnutrition rates among children under five. Health clinics in ASAL counties typically face stock and staffing pressures during drought cycles; an increase in malnutrition caseloads would require scaled-up therapeutic feeding and logistics. Failure to move resources quickly drives costs up—treatment is always more expensive than prevention. FEWS NET and NDMA bulletins repeatedly highlight nutrition as an immediate secondary impact of rainfall deficits.

Local governments must prepare for displacement and conflict. Migration from hardened ASAL to peri-urban areas and better-watered highlands strains local services, while resource competition raises conflict risk. Counties with porous borders to Somalia, Ethiopia, and South Sudan face cross-border pastoral movement that complicates response and security coordination. Early planning between county administrations and national response units is essential to avoid escalation.

Supply chains and transport: poor or erratic rains can damage rural roads during intense downpours in the wetter pockets, and conversely, prolonged dry seasons increase dust and wear, raising transport costs. Either dynamic raises the price of moving food to markets and limits the private sector’s ability to smooth regional supply shocks. Logistics costs will therefore be a transmission channel from weather to retail food inflation.

For exporters, horticulture firms in the highlands may benefit from localized above-normal rainfall, but only if rains come in a pattern that supports field operations rather than causing waterlogging at harvest. Exporters of fresh produce remain vulnerable to weather-related harvest timing and quality; buyers and insurers will be monitoring crop progression closely.

Banking and credit risks will rise in drought-affected counties. Microfinance institutions and commercial banks with agricultural loan books concentrated in ASALs will see higher default risk as borrowers’ incomes fall. Lenders should increase portfolio monitoring and consider restructurings or targeted liquidity facilities to avoid forced asset sales and negative social outcomes.

Read Also: Kenya Met Warns Of Cold Nights, Rainfall In The Following Counties This Week

Insurance uptake (parametric and index insurance) is a policy lever that could blunt shocks, but penetration remains low. The current forecast is a reminder to regulators and private insurers to accelerate scalable index-based products tied to rainfall or normalized vegetation indices; these are cheaper and quicker to pay out than traditional indemnity claims. Donors and DFIs can catalyze demand by co-paying premiums for vulnerable smallholders.

Read Also: Kenya Met Forecasts Rainfall In Several Regions Over The Next Seven Days

Market sizing: if ASAL production and pastoral productivity decline as forecast, the likely national impact is reduced livestock exports and higher domestic meat prices, small reductions in national maize supply (depending on planting decisions), and pressure on national cereal reserves. Strategic reserves and import plans should be reviewed now to avoid reactive, expensive procurement later.

Political risk is real. Food-price shocks and visible failures of county drought response have precipitated instability in Kenya’s recent past. A season where some counties appear to prosper while others suffer will amplify narratives of marginalization and could influence political mobilization ahead of local or national contests. Fund managers and corporates should factor local governance capacity into their country risk assessments.

Agricultural extension and climate advisories matter more than ever. County agriculture departments and KMD/NDMA should push targeted advisories now: drought-resilient crop varieties, timing of planting windows, water harvesting, and livestock destocking/feeding strategies. Timely information can materially change outcomes for both yields and livestock survival. ICPAC and NMHS collaborations are already aimed at this, but dissemination gaps persist at local levels.

Policy recommendations — immediate (30–90 days). 1) Scale up targeted cash transfers in flagged counties (NDMA/HSNP coordination). 2) Pre-position therapeutic food and emergency veterinary supplies. 3) Announce conditional fiscal reprioritizations for drought response to reassure markets and households. 4) Activate inter-county water resource sharing and livestock corridor management to reduce conflict and stress migration. These steps reduce humanitarian cost and market disruption if implemented early.

Policy recommendations — medium term (6–18 months). Invest in water harvesting (dams, sand dams), expand index insurance and grain-reserve mechanisms, and accelerate renewable energy build-out (solar and geothermal) to reduce hydro dependence and energy price vulnerability. Strengthen county-level early warning systems and market linkages so localized surplus can reach deficit areas quickly and affordably.

What investors should do now. Agribusiness funds should re-weight portfolios to include drought-resilient value chains (pulses, drought-tolerant seeds, animal feed processing). Energy investors should accelerate distributed solar and storage projects that reduce exposure to hydropower variability. Financial investors should pressure portfolio companies for climate risk disclosure and contingency plans for supply-chain interruptions.

What humanitarian actors should do. Pre-finance food procurement where possible (to avoid market crowding), expand mobile cash programmes for flexibility, scale community veterinary work to reduce livestock losses, and coordinate with county governments for targeted feeding and water trucking where needed. Early action costs far less than a late response.

How this could play out — two scenarios. Best case: above-normal rains in western and highland pockets materialize, ASAL counties receive timely, limited showers, and NDMA/NDPC pre-emptively scale cash transfers — market impacts are muted and inflation eases slightly into 2026. Worst case: Western rains come but fail to reach ASALs; livestock losses accelerate, humanitarian caseloads rise, energy costs tick up if hydro inflows weaken, and budget reallocation increases borrowing or squeezes capital projects. The forecast currently tilts toward the downside for ASALs.

Data gaps and uncertainty. Seasonal forecasts are probabilistic, not deterministic. Localized mesoscale weather (timing and intensity), soil moisture memory from earlier rains, and human decisions (planting dates, destocking) will determine the realized impact. Continuous monitoring from ICPAC, KMD, NDMA, and FEWS NET should drive rolling decisions — but trustworthy local dissemination remains the key bottleneck.

Bottom line for Kenya. The OND outlook is a warning: expect uneven outcomes. Western and highland pockets could produce relief for local markets, but most of Kenya’s ASALs face a credible risk of continued stress. The economic consequences will be felt in food prices, livestock export volumes, energy costs, and fiscal pressures. Early, targeted action by national and county governments — supported by donors and the private sector — can blunt the worst impacts, but the time to act is now.

Read Also: Kenya Met Issues Weekly Weather Forecast, The Following Regions To Receive Prolonged Rainfall

About Steve Biko Wafula

Steve Biko is the CEO OF Soko Directory and the founder of Hidalgo Group of Companies. Steve is currently developing his career in law, finance, entrepreneurship and digital consultancy; and has been implementing consultancy assignments for client organizations comprising of trainings besides capacity building in entrepreneurial matters.He can be reached on: +254 20 510 1124 or Email: info@sokodirectory.com

- January 2025 (119)

- February 2025 (191)

- March 2025 (212)

- April 2025 (193)

- May 2025 (161)

- June 2025 (157)

- July 2025 (226)

- August 2025 (211)

- September 2025 (270)

- October 2025 (223)

- January 2024 (238)

- February 2024 (227)

- March 2024 (190)

- April 2024 (133)

- May 2024 (157)

- June 2024 (145)

- July 2024 (136)

- August 2024 (154)

- September 2024 (212)

- October 2024 (255)

- November 2024 (196)

- December 2024 (143)

- January 2023 (182)

- February 2023 (203)

- March 2023 (322)

- April 2023 (297)

- May 2023 (267)

- June 2023 (214)

- July 2023 (212)

- August 2023 (257)

- September 2023 (237)

- October 2023 (264)

- November 2023 (286)

- December 2023 (177)

- January 2022 (293)

- February 2022 (329)

- March 2022 (358)

- April 2022 (292)

- May 2022 (271)

- June 2022 (232)

- July 2022 (278)

- August 2022 (253)

- September 2022 (246)

- October 2022 (196)

- November 2022 (232)

- December 2022 (167)

- January 2021 (182)

- February 2021 (227)

- March 2021 (325)

- April 2021 (259)

- May 2021 (285)

- June 2021 (272)

- July 2021 (277)

- August 2021 (232)

- September 2021 (271)

- October 2021 (304)

- November 2021 (364)

- December 2021 (249)

- January 2020 (272)

- February 2020 (310)

- March 2020 (390)

- April 2020 (321)

- May 2020 (335)

- June 2020 (327)

- July 2020 (333)

- August 2020 (276)

- September 2020 (214)

- October 2020 (233)

- November 2020 (242)

- December 2020 (187)

- January 2019 (251)

- February 2019 (215)

- March 2019 (283)

- April 2019 (254)

- May 2019 (269)

- June 2019 (249)

- July 2019 (335)

- August 2019 (293)

- September 2019 (306)

- October 2019 (313)

- November 2019 (362)

- December 2019 (318)

- January 2018 (291)

- February 2018 (213)

- March 2018 (275)

- April 2018 (223)

- May 2018 (235)

- June 2018 (176)

- July 2018 (256)

- August 2018 (247)

- September 2018 (255)

- October 2018 (282)

- November 2018 (282)

- December 2018 (184)

- January 2017 (183)

- February 2017 (194)

- March 2017 (207)

- April 2017 (104)

- May 2017 (169)

- June 2017 (205)

- July 2017 (189)

- August 2017 (195)

- September 2017 (186)

- October 2017 (235)

- November 2017 (253)

- December 2017 (266)

- January 2016 (164)

- February 2016 (165)

- March 2016 (189)

- April 2016 (143)

- May 2016 (245)

- June 2016 (182)

- July 2016 (271)

- August 2016 (247)

- September 2016 (233)

- October 2016 (191)

- November 2016 (243)

- December 2016 (153)

- January 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (4)

- March 2015 (164)

- April 2015 (107)

- May 2015 (116)

- June 2015 (119)

- July 2015 (145)

- August 2015 (157)

- September 2015 (186)

- October 2015 (169)

- November 2015 (173)

- December 2015 (205)

- March 2014 (2)

- March 2013 (10)

- June 2013 (1)

- March 2012 (7)

- April 2012 (15)

- May 2012 (1)

- July 2012 (1)

- August 2012 (4)

- October 2012 (2)

- November 2012 (2)

- December 2012 (1)